The extensive and hugely varied Loire wine region can be difficult to get to grips with, so we’ve put together this Loire Fast Facts feature to provide a clear insight into the region and its wines. As it’s such a large and diverse region, we have divided it into the four main sub-regions and prepared fast fact features for each. Our guide to the Loire includes an overview of the region to give you some initial insight, while the fast facts for each area enter into greater detail.

Photo credit: Domaine des Génaudières, Pays Nantais

Where is it?

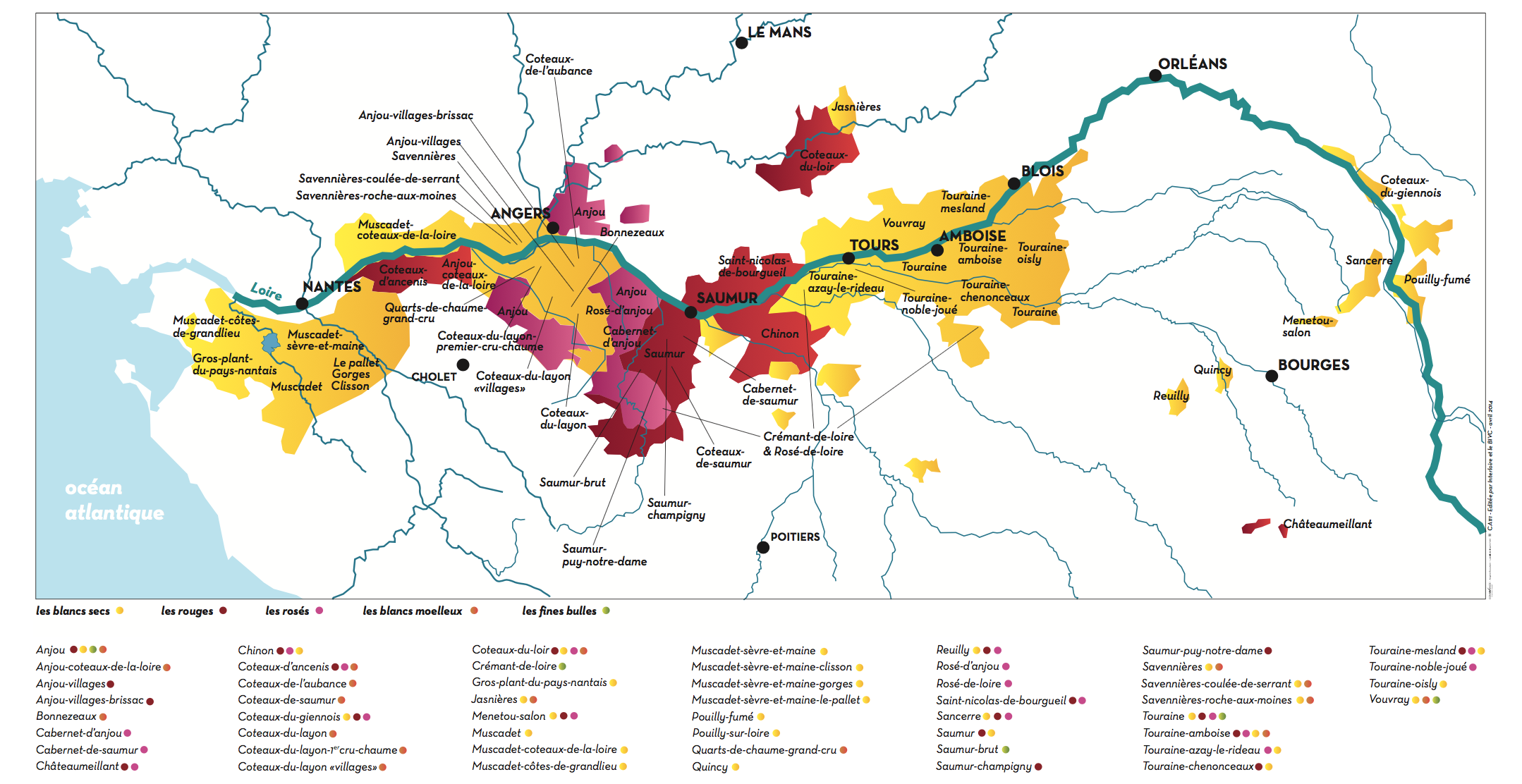

The Loire is one of France’s biggest wine regions, following the course of the Loire (France’s longest river, with a total length of 1,000 km) until it reaches the Atlantic Ocean, off the coast of Brittany. The Loire River is roughly in the centre of France and crosses major historical cities, including Orléans, Blois, Tours and Angers. The map below from Loire Valley Wines (the official website of the Interloire organization) gives you a good idea of the size of this region.

Loire Valley Key Figures

- No. 1 Biggest producer of French AOC white wines

- No. 1 Biggest AOC region for French sparkling wines (excluding Champagne)

- No. 2 Second biggest producer of French AOC rosé wines

- No. 3 Third in France in terms of production with 2.4 million hectolitres

- No. 4 Fourth biggest French region in terms of wine-growing area – 70,000 ha

- 61 Appellations and Denominations

- 420 million bottles per year.

- 4,000 wineries

- 160 trading companies

- 15 cooperatives

Source: 2016 figures from the website of the Loire Valley Wine Bureau, which is the marketing representative of Interloire and the Bureau Interprofessionnel des Vins du Centre (BIVC) in the United States.

The sub-regions of the Loire

The Loire River and its many tributaries play a key role in climate fluctuation and wine diversity throughout the wine-producing district. The region stretches from the Central Loire, which is very much in the centre of France, to the south of Paris and has a semi-continental climate with greater temperature fluctuations, and, as you travel westwards along the river towards the Atlantic Ocean, the climate becomes more maritime, with more moderate temperatures and greater humidity.

The Loire wine-producing district is divided into 4 main regions :

Pays Nantais

This is the westernmost sub-region and the most influenced by the Atlantic. This is an area with rocky soils and a moderate, moist climate. Melon de Borgogne is the most-grown grape, made into dry white wines known as Muscadet that pair well with seafood.

Click here for our Fast Facts Feature on Pays Nantais.

Photo credit: Château de Chasseloir, situated on the River Maine in Pays Nantais

Anjou-Saumur

These are two smaller regions that together make up the next sub-region, which still has a maritime influence. This is a very varied area in terms of mesoclimate and soils, with a wide range of grape varieties and wine styles. Key among them are white wines (sweet, dry, still and sparkling) made from Chenin Blanc and reds and rosés from Cabernet Franc and other varieties.

Click here for our detailed guide and Fast Facts Feature on Anjou-Saumur.

Photo credit: Domaine du Petit Metris, Anjou

Touraine

This is the next sub-region along and marks the transition point between climate type – this becomes more continental – soils, grapes and wines. This area is most known for its Chenin Blanc and Cabernet Franc wines but also produces good Sauvignon Blanc, rosé and sparkling wines.

Click here for our Fast Facts Feature on Touraine.

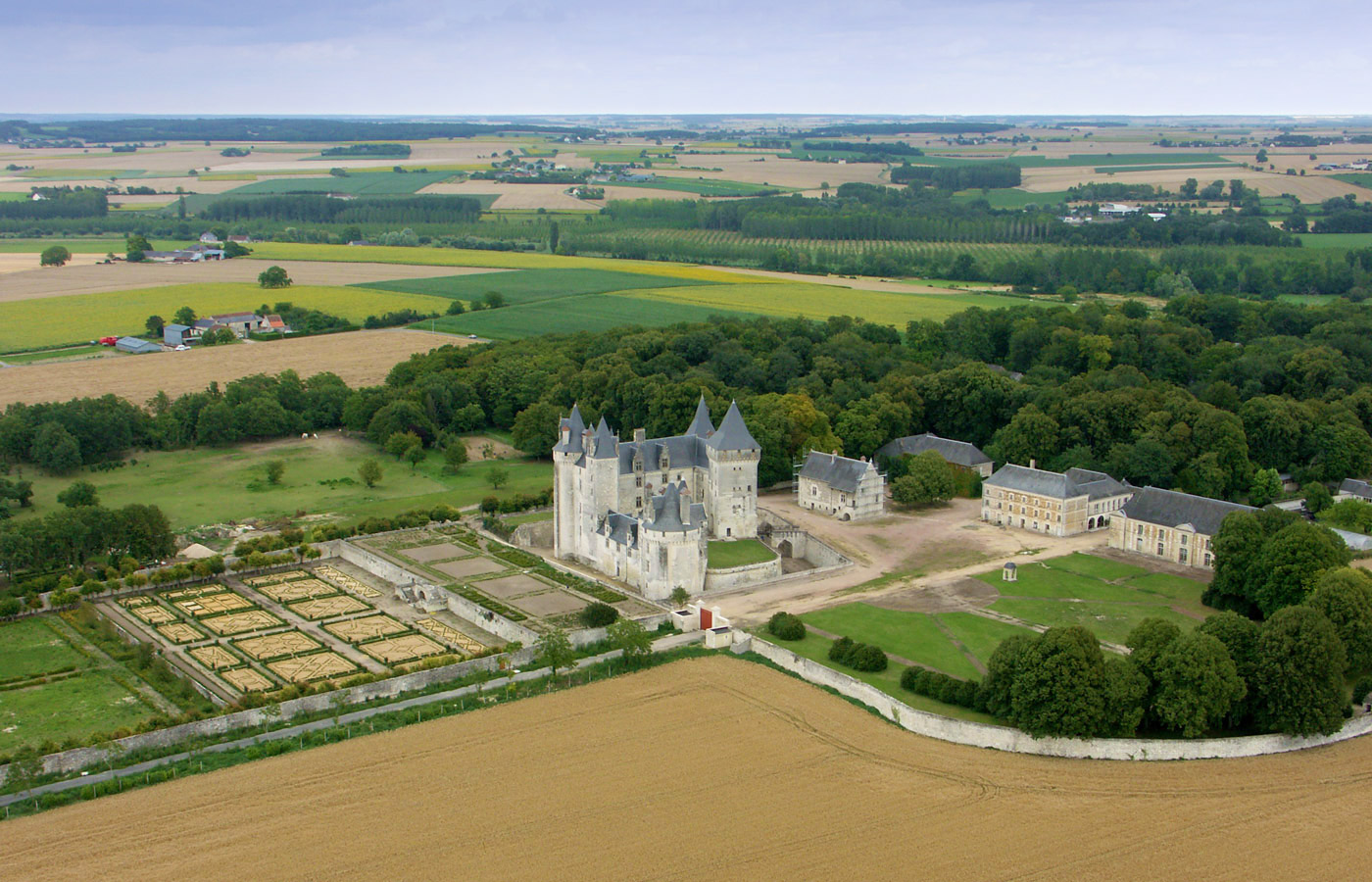

Photo credit: Château du Coudray-Montpensier, Chinon in the Touraine

Central Loire

The Central Loire is the furthest inland and the climate is sub-continental with significant temperature differences. The soils are varied and include some Kimmeridgian clay, so in terms of climate and soils, the Central Loire has plenty in common with Chablis in Burgundy, just 100km away. The Central Loire is renowned for its Sauvignon Blanc, though it also produces some red wines.

Click here for our detailed guide and Fast Facts Feature on the Central Loire.

Photo credit: Berry Province tourism development project

Viticulture and winemaking

The region has a lot of small vineyard areas, many of which are family-owned.

Viticultural methods vary but many have adopted sustainable techniques, including organic or biodynamic production.

Guyot training is common across all sub-regions.

Viticultural challenges vary by sub-region; botrytis and other fungal problems can arise in the humid conditions in some sites in Pays Nantais and Anjou while spring frost can be more of an issue in the continental climate of Touraine and Central Loire.

Renaissance

Producers in the Loire have had to become more competitive in recent decades and this has led to a renaissance in all aspects of grape-growing and wine production, including:

- a range of techniques to control vine vigour and ensure lower yields so that the grapes that are harvested are riper and have more aromas and flavours.

- taking care to harvest riper grapes, even though this may mean making several passes through the vineyard, for intance with Chenin Blanc, which tends to ripen unevenly.

- Winemakers are experimenting with techniques to produce more exciting wines, including:

- some skin contact for white wines,

- increasing use of oak (some new) for fermentation and/or ageing for both whites and reds

- better extraction of tannins and colour for red wines

- partial or complete MLF in white wines

- leaving some whites over their lees to add complexity and texture

Loire guide: Grape varieties and wine styles

There are a very wide variety of grape varieties grown across the Loire region and these are detailed in the fast facts feature for each sub-region.

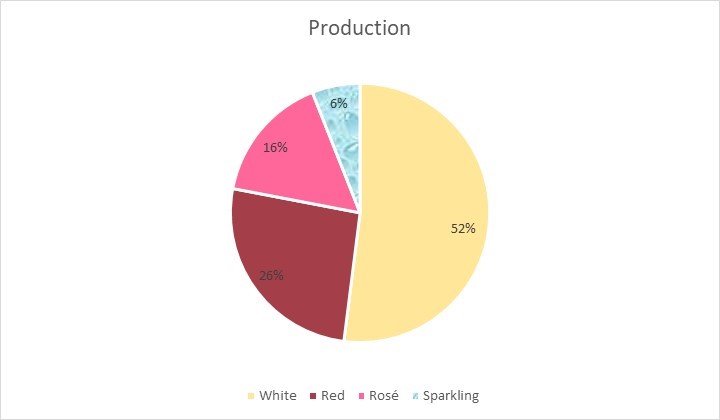

White wines account for over half of the region’s production and can vary from bone-dry to lusciously sweet. The region is also an important producer of red, rosé and sparkling wines.

Source of data for pie chart: Jancisrobinson.com

Loire guide: History

The first vineyards were planted by the Romans in the Nantes area, but viticulture in the Loire began to grow from around 500 A.D. onwards. As was the case in the rest of France, the production of wine and the habit of consuming it tended to spread with Christianity, as each new abbey or monastery that was founded planted its own vineyards.

Proximity to a river has always been an important factor in viticulture because of the water’s moderating effect on the climate and its ability to increase solar exposure in areas where grapes might not otherwise ripen. But historically, there was an even more critical reason for planting vineyards near rivers: the ability to transport the wine at a time easily and quickly by boat or barge, when the alternative was a horse-drawn cart ambling slowly along poor-quality roads. It is therefore no coincidence that viticulture spread along the Loire and its tributaries rather than into areas further away from the river. As it grew, the wine that wasn’t locally consumed was shipped downriver to Nantes and much of this was exported on the ships carrying locally extracted salt to different markets in northern Europe.

The big break for wine producers in the Loire came in 1154 when Henry Plantagenet, Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou, became King of England. He served wines from the Loire at court and helped create demand for them in England.

The French Revolution had a huge impact on wine production, by sweeping away some of the restrictions and taxes that had existed before and also, very importantly, by transforming land ownership in France. The two main reasons why today small (or even tiny) vineyard holdings are common in much of France, including the Loire, have their roots in the changes that took place at that time. Firstly, the property of the church and the aristocracy and anyone who emigrated from France during the revolution was seized and auctioned off in small lots with the goal of raising the maximum amount of money. Those who were able to buy these properties, including vineyard areas, were mostly reasonably well-off middle-class people.

Secondly, a law was passed in 1793 which decreed that when a person died, his or her possessions should be divided equally among all offspring, regardless of gender or age. This meant that with each generation, a plot of land would be further sub-divided. Many a fair-sized family holding in France has thus gradually been divided to the point where many individuals each own just a few rows of vines.

In the late 19th century, phylloxera devastated many of the vines in the Loire, as elsewhere across Europe. Viticulturists slowly replanted their vineyards, using the American rootstocks that could resist this devastating louse. And it was then that vineyards took on the form that we take for granted today – neat rows of vines, all of the same variety – rather than the intermingled “field blends” that had previously been planted in no particular pattern.

Photo credit: Domaine de Beauséjour, Chinon

Loire guides & useful resources:

Phillips, R., 2016. French Wine: A History. Oakland: University of California Press.

Robinson, J., 2015. The Oxford Companion to Wine. 4th Ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.