Once upon a time, many people thought the UK was too cold for serious winemaking and English wine was ridiculed. But in the light of the rapidly growing viticulture industry in both England and Wales, it is time to think again. We’ve pulled together this England and Wales Fast Facts feature so that you can get to grips with emerging wine regions in England and Wales, and both Welsh and English wines.

Where is it?

Part of the United Kingdom, England and Wales are located to the south of Scotland on an island in northern Europe, which is situated to the east of Ireland, west of Scandinavia and north of France. Wine production is concentrated in England, particularly the south, although there are a number of vineyards in northern England and Wales.

The Essentials of Terroir

Climate & Landscape

The climate has a strong maritime influence. The Gulf Stream brings warm water from the Southern Hemisphere, moderating the temperature, so that the UK experiences milder weather year-round than would otherwise be the case at this latitude. The current also causes frequent changes in pressure and unsettled weather, which can vary significantly even in a single day. Prevailing winds from the west bring rain throughout the year, sometimes accompanied by stormy weather and high winds and the climate is, therefore, wetter in the west and drier in the east.

While there has been small-scale viticulture and Welsh and English wine production for many years, the climate in the UK used to be considered too marginal for large-scale production but climate change means that springs and summers are a little warmer than before, making it easier to ripen grapes. Also pruning, training and canopy management techniques, together with improved knowledge about choosing the right grape for the site help make viticulture much more viable.

Temperatures

Temperatures

Average temperatures can vary between 0˚C in February and 21˚C in July and August, though in recent years temperatures have sometimes been significantly outside this range.

Rainfall

This varies significantly but the average for England is 855 mm per year.

Other Climate Notes

Spring frost can appear as late as May, which can lead to the loss of new shoots, reducing yields.

Rain and/or wind can have an impact during flowering, reducing fruitset, or at any time during the ripening period or harvest, causing a range of problems – grapes can be blown off in high winds, damp weather can lead to the onset of fungal diseases, rain can cause ripe grapes to swell, diluting their flavour and making them prone to burst and attract pests or disease.

A cool, cloudy summer can mean that grapes struggle to ripen fully, leading to tartly acidic wines with herbaceous rather than fruity aromas and flavours, light colour and body and low alcohol content.

Soils

The soils vary significantly across the UK’s different vineyards, though many tend to have reasonably free-draining soils because vines hate sitting in water and moreover, clay soils are slow to warm in spring and therefore don’t favour vine development in the UK. Sandstone and sandy limestone often occur in southern England, for instance, while some sites in North Wales have shale or slate.

However, in English wine it is the chalk soils that everyone is talking about. It is the availability of land in southern England with similar soils to Champagne that what has drawn investors (including two Champagne houses) to buy land and plant the traditional Champagne varieties in that area. They believe that the soil (together with the similarly cool climate) will lead to the production of grapes with similar characteristics to Champagne and thus the production of quality sparkling wines.

Champagne and southern England share the same soil type because they are geologically part of the Paris Basin, which extends from southern England across the channel to Burgundy and Champagne. This is an area of chalk, limestone and other sediments containing decomposed sea creatures and minerals left behind when the sea receded millions of years ago. Chalk is a great bonus as it is sufficiently porous to allow water to drain away, without vine roots becoming waterlogged but retains enough moisture to help the vines survive drought. Chalk soils have a high lime content, which influences the type of rootstock that growers use, as they need one that is both lime-resistant and phylloxera-resistant and that copes well with the cool, northerly climate.

Longitude

0.2˚W at Bolney in Sussex.

Latitude

51˚N at Bolney in Sussex.

Altitude

Up to 150 metres above sea level. Because this is such a northerly climate and temperature falls the higher up you go, viticulture generally becomes unviable above this height in the UK.

Viticulture Facts & Vineyard Management

Irrigation

With year-round rain, irrigation tends not to be an issue in the UK but can be important for newly planted vines during periods of drought.

Vine Training systems

A number of systems are in use in the UK, mostly designed to control vigour and enable canopy management to ensure that grapes get sufficient exposure to the sun.

Pests and Diseases

- Cool, damp weather is great for fungal diseases like powdery mildew, downy mildew, and botrytis.

- Trunk diseases are widespread and Phomopsis, Esca and Eutypa can all be found in the UK.

- Rabbits, slugs and snails can damage young plants and buds and birds can strip the harvest.

Viticultural Challenges

Given the challenges presented by low temperatures, northerly latitude, frost, wind and rain, most vineyards are situated on south-facing slopes to maximize solar exposure, above any frost pocket and ideally protected from winds by hills and/or trees.

Shop selling only English wine

Winemaking: Welsh & English wine

Sparkling wine – particularly traditional, in-bottle fermentation styles – are now the most common style produced in the UK. In fact, sparkling wine accounts for 66% of all English and Welsh wine produced and has gained global recognition for its quality. The cool climate favours this, as the low temperatures make for high acidity and moderate sugar levels which are ideal for sparkling wine.

The climate also means that the UK tends to produce white, rosé and light-bodied red wines, generally with high levels of acidity and moderate alcohol – indeed sugar is often added to musts (a process known as chaptalization) to increase the alcohol level to 11.5% or 12%. The wines may or may not undergo malolactic fermentation to soften the tart acidity. Low temperature fermentation in stainless steel tanks is common to encourage the development of fruity aromas. Some wines make experience some oak-ageing.

Grape Varieties in Welsh & English wine

The Champagne varieties

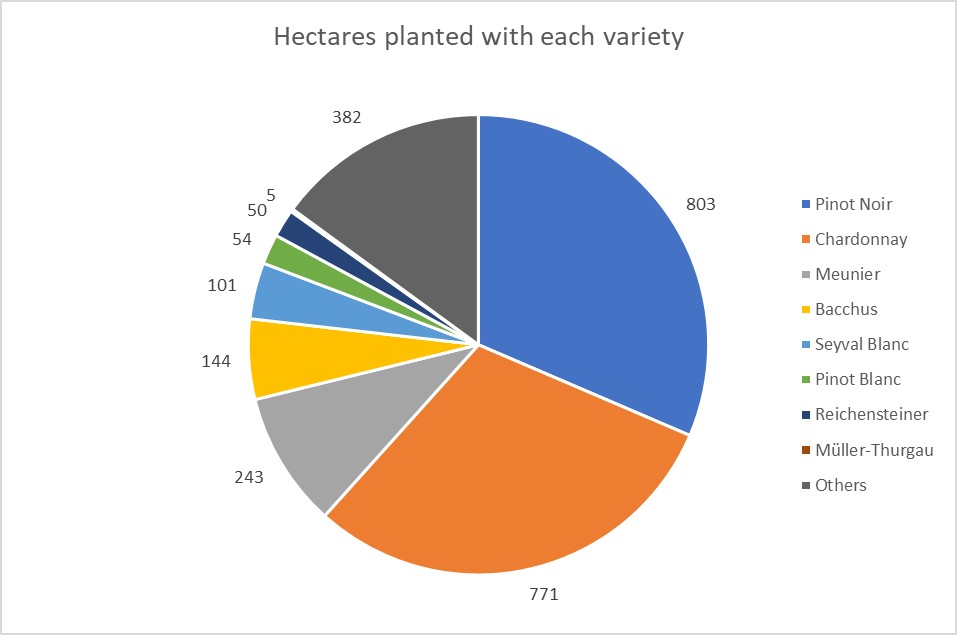

As is clear from the chart above, the three Champagne varieties now account for 71% of all the grapevines planted.

Chardonnay

White variety Chardonnay is considered to be good at expressing the terroir of where it is grown and it also takes well to different winemaking techniques, so the wines can vary enormously. In the UK, it is primarily planted for use in sparkling wine, where it can yield delicate, citrus flavours turning into biscuit and brioche with extended lees ageing. It is early budding and ripening, productive and easy to grow. However, it is susceptible to millerandage and coulure in poor weather and botrytis bunch rot in rainy harvests.

Pinot Noir

In the marginal climate and chalky soils of southern England, as in Champagne, Pinot Noir can achieve very fine expression, adding body, length, structure and red fruit aromas and flavours to a sparkling wine. Pinot Noir is notoriously tricky to grow well, in warmer climates rushing to maturity with excess sugar and overripe flavours, while it is prone to rot in damp weather and, being early budding, can lose much of its yield to spring frosts, rain or other inclement weather.

Meunier

The much-maligned underdog of the Champagne grape trio, Meunier is an obliging variety that ripens even in bad years, when the Pinot Noir and Chardonnay may not. Meunier is higher in acidity and lower in alcohol than Pinot Noir. It can be fruity and the sparkling wine can gain an aroma of warm bread or boulangerie.

The rest… Other grape varieties in Welsh & English wine

Pinot Blanc

This variety can be overlooked, but it is a pest- and disease-resistant variety that gives good yields and can be rather similar to Chardonnay but perhaps lighter in body and not quite as complex. In a cool climate like the UK, it will reveal green fruit and citrus aromas and be high in acidity. Like Chardonnay, Pinot Blanc can cope with oak fermentation or ageing, time over its lees and malolactic fermentation, if they winemaker wishes to add complexity or body to the wine.

Bacchus

This white variety is a cross between Silvaner x Riesling and Müller-Thurgau which has usefully high sugar levels but is low in acidity. If it manages to ripen fully, it is very aromatic with notes of elderflower and pears. It is also grown in Germany but some of the best examples are from the UK.

Seyval Blanc

Seyval Blanc

This is a hybrid between Seibel 5656 and Seibel 4986 and is relatively disease-resistant, with good yields. It also ripens early, which can be a blessing if wet weather appears in early autumn. The wines have citrus aromas, like grapefruit, are light in body and high in acidity. If aged in oak barrels, the wines become softer and fuller-bodied. This is one of the most successful varieties in the UK, with austere young wines gaining a honeyed richness with age.

Reichensteiner

Another German cross, this time between Müller-Thurgau and Madeleine Angevine x Early Calabrese. It is resistant to rot and achieves good sugar levels but can produce dull and neutral wines.

Müller-Thurgau

This white, lightly aromatic variety is a cross between Riesling and Madeleine Royale. It has citrus fruit and some Muscat-type aromas and low to medium acidity. It ripens easily and is high-yielding unless the vigour is controlled. When the yields are too high, the wines can be dull and lacking in acidity.

Phoenix

This is a disease-resistant cross between Bacchus and Villard Blanc invented in 1992 in Germany. It produces herbaceous, aromatic white wines.

Solaris

This is a non vinifera hybrid, which is an early-ripening, vigorous and high-yielding white variety. It has good resistance to fungal disease and frost but is susceptible to botrytis bunch rot. The wines tend to have a medium level of acidity and are lightly fruity with aromas of bananas and hazelnuts.

Ortega

This is a cross between Müller-Thurgau and Siegerrebe and is popular because it develops higher levels of sugar than other varieties in a cool climate, boosting the potential alcohol level of the wine. It produces a white wine that tends to be low in acidity, with aromas of grapefruit and elderflower.

Muscat Blue

A vigorous black vinifera variety often grown as a table grape, Muscat Blue has large, blue, aromatic grapes.

Rondo

Another hybrid, this is a black variety that is early-ripening and reliable with good yields. It has high frost and disease resistance but is prone to powdery mildew. Its large leaves need to be kept under control to ensure that they don’t shade the grapes from the sun. The wines tend to have good levels of acidity, light body and soft tannins. When aged in oak, it gains aromas of smoke and toast. Malolactic fermentation lends the wine a creamy texture.

Traditional Wine Pairing for Welsh & English wine

Sparkling wine pairs well with many types of food. Check it out with a traditional meat terrine or a cheese platter.

A dry white like Seyval will pair well with seafood, while a rosé is good as an appetizer or with salad.

Production Area

In 2017, there were 2554 hectares of vineyard and this is growing fast. A million vines were planted in 2017 and the figure for 2018 is expected to be even higher.

Number of English Wine & Welsh Wine Producers

- 147 wineries

- 502 commercial vineyards

Annual Production

3.86 million bottles of sparkling and still wine made in UK vineyards were released for sale in 2017, up 64% on 2016 when 2.36 million bottles were released. Compare this to the 1.34 million bottles released for sale in 2000. Production in 2017 was higher again, at 5.9 million bottles.

Main Regions / Appellations

- South-West England has 290.8 hectares

- South-East England has 1923 hectares

- East Anglia 130.5 hectares

- Other parts of England have 166.5 hectares

- Wales has just 42.3 hectares

The UK has followed the EU system of Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) for Quality Wines and Protected Geographical Indication (PDI) for Regional Wines. Those wines without a geographical indication are varietal wines, while others that do not include variety or origin on the label are just called UK Wine.

Welsh & English Wine Business

Welsh & English Wine Business

The UK wine industry continues to consist mainly of many small wineries but the arrival of two major Champagne Houses – Taittinger in Kent and Pommery in Hampshire – has set the tone for further expansion with larger companies and foreign investors likely to become part of the picture in future.

Wine tourism and cellar door sales are also growing fast in the UK and are seen as an important income stream for many English and Welsh vineyards.

Interesting Facts: English wine

Wine consumption and production in England date back many centuries but the first record of winemaking comes from the spread of monastic orders in the 6th and 7th centuries with The Venerable Bede writing “wines are cultivated in several localities” in his Ecclesiastical History of 731.

Sources

Clarke, O. & Rand, M. Grapes and Wines. 2015 edition. London: Pavilion.

Robinson, J., 2015. The Oxford Companion to Wine. 4th Ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

http://www.wsta.co.uk/press/904-2017-was-a-record-breaking-year-for-uk-wine-releases

https://www.wsetglobal.com/knowledge-centre/blog/2016/february/19/the-rise-of-english-wine/

https://www.winegb.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/WineGB-Infographics-May-2018.pdf

http://www.emr.ac.uk/newsletter/contemporary-uk-viticulture-counterbalancing-climate-challenges/