South America’s wine regions don’t ever sit still. They are constantly on the move and in the last two decades we have seen several new wine regions emerge in previously unimaginable locations: the Atacama desert, Patagonia and in the heights of the Andes mountains where Inca ruins lie. Last week I gave a masterclass and South America tasting at the London Wine Fair to discuss and demonstrate exactly how far producers are pushing the boundaries.

You can watch the full masterclass here (and you can thank my lovely brother for filming it and adding the pretty flowers/paw prints on the corners 😊).

I was honoured to be able to present on behalf of the Circle of Wine Writers and absolutely thrilled to see so many esteemed colleagues and wine experts attend the tasting. I can tell you it is just a little bit more nerve-racking when you have Steven Spurrier in the front row!

The greatest honour of all was to be able to present these producers’ wines, all of whom went to great efforts to send them half way around the globe to make the tasting in time. So I wanted to share some insight into why I picked the flight we tasted, and why these wines demonstrate how South America’s winemaking and viticultural boundaries are being broken.

South America masterclass wines: Pushing the boundaries

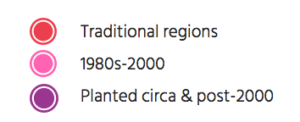

I split my South America tasting into the three frontiers of traditional viticulture that are being challenged: the Patagonian frontier, the coastal frontier and the altitude frontier. For each map I’ve indicated where new plantations are happening and where traditional regions are.

I split my South America tasting into the three frontiers of traditional viticulture that are being challenged: the Patagonian frontier, the coastal frontier and the altitude frontier. For each map I’ve indicated where new plantations are happening and where traditional regions are.

Wines are in order of service (which you can follow on the video link above too).

The Patagonian Frontier

Patagonia is a shared territory between Chile and Argentina, and in wine terms Patagonia begins at Rio Negro and Neuquén in Argentina and in Chile, where they are a little more modest, we consider the Osorno area the beginning of Patagonian wines (rather than Bio Bio, which is almost parallel to Neuquén).

Patagonia is a shared territory between Chile and Argentina, and in wine terms Patagonia begins at Rio Negro and Neuquén in Argentina and in Chile, where they are a little more modest, we consider the Osorno area the beginning of Patagonian wines (rather than Bio Bio, which is almost parallel to Neuquén).

On the Chilean side, Patagonia is cool and wet, whereas on the Argentine side, Patagonia is cool and dry. There have been developments on either side which are exciting and commercial wine releases from Viedma, Chubut and the Osorno region, and there are experimental plantations even further south, including at Chile Chico – which is the southernmost vineyard in the world.

Casa Silva, Lago Ranco Riesling 2016

Casa Silva is a long-running family-owned winery in Colchagua. They make plenty of wine and have a wide, quite classic, portfolio from the Central Valleys, so it impressed me when they stuck their necks out to make a wine from virgin territories in Patagonia – on the family estate at Lago Ranco. Climate change is making Patagonia more viable for wine production. However this site also uses the moderating effect of the lake and they planted their vines on the volcanic slopes for better exposure and drainage. Casa Silva produce smart Sauvignon Blanc and Pinot Noir wines from Lago Ranco and this Riesling is the newest release – only launched a couple of months ago. It’s part of a very exciting tribe of Rieslings coming from Chile today (not just from Patagonia, but also the Andes and the coast) and I think it shows great typicity of the variety but also of the place – with some of the more delicate aromatics you get in the south and a spine of acidity. A harmonious wine and an exciting addition to the growing Lago Ranco portfolio.

Stainless steel tanks. Alc. 11.5%

pH: 3.01 , Total Acidity: 5.8

Residual Sugar: 9 g/L

Casa Silva: www.casasilva.cl

£20, www.jnv.co.uk

The Coastal Frontier

Coastal vineyards and wine regions are certainly the fasting growing in South America, and that is largely to do with Chile. However coastal wine regions in Chile are surprisingly young, only starting in the 1980s when Pablo Morande pioneered a vineyard in Casablanca. Since then, however, we have seen extensive coastal vineyard plantations in Chile, most notably in Casablanca, neighbouring San Antonio (where sub-region Leyda is well-known) and in Limarí further north. The coastal mountain range in Chile runs along all the Central Valley regions and there have also been several coastal developments in the traditionally Entre Cordillera or Andes wine regions of Colchagua and Aconcagua (where the coastal wine regions are Colchagua Costa and Aconcagua Costa). I also marked Itata and Maule on the map because some new vineyards are being planted there practically facing the coast, which is another exciting coastal development.

Coastal vineyards and wine regions are certainly the fasting growing in South America, and that is largely to do with Chile. However coastal wine regions in Chile are surprisingly young, only starting in the 1980s when Pablo Morande pioneered a vineyard in Casablanca. Since then, however, we have seen extensive coastal vineyard plantations in Chile, most notably in Casablanca, neighbouring San Antonio (where sub-region Leyda is well-known) and in Limarí further north. The coastal mountain range in Chile runs along all the Central Valley regions and there have also been several coastal developments in the traditionally Entre Cordillera or Andes wine regions of Colchagua and Aconcagua (where the coastal wine regions are Colchagua Costa and Aconcagua Costa). I also marked Itata and Maule on the map because some new vineyards are being planted there practically facing the coast, which is another exciting coastal development.

The most traditional and oldest coastal region of South America is, of course, Peru. However Uruguay is probably the most extensive traditional coastal region, with its main wine region Canelones only some 40km from the coast. Uruguay has seen much more coastal development happening further along the coastline in recent years, and Argentina is now producing its very first coastal wines ever.

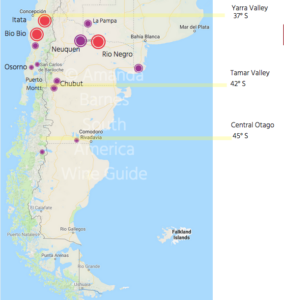

Bodega Bouza, Pan de Azucar Riesling 2016

Bodega Bouza is a family winery that became well known for their Albariño, which they produce near Montevideo and Canelones, a bit further inland. However the wine I picked is from their young Pan de Azucar vineyard in Maldonado – one of Uruguay’s newest and most important coastal regions. They have a handful of great wines coming from this 2010 vineyard, including super Tannat and Merlot, but we tasted their Riesling which I think has fantastic Riesling typicity but also a really great weight on the palate and distinct character, not only due to its maritime influence but also for its special syenite soils. Uruguay is a playground of different soil types – incredibly diverse for its diminutive size – and this wine exemplifies the movement happening in Uruguay today where producers are looking for new terroirs that can produce exciting wines. This wine was one of the favourites of the tasting.

Stainless steel tanks. Alc. 13.5%

pH: 3.29, Titratable Acidity: 4.1

Residual Sugar: 1.5 g/L

Bodega Bouza: www.bodegabouza.com

£20, www.laytons.co.uk

Costa y Pampa Sauvignon Blanc 2017

This is a really exciting project for Argentina, and I’m happy to explain why. Although the wines are quite classic in style, these are the first and practically the only coastal wines that exist in Argentina. Owned by Trapiche, one of the biggest wine producers in Argentina, this is a more boutique affair with 25 hectares planted in Chapadmalal, Buenos Aires province. There is a mild, maritime climate, as it’s only 6 kilometres from the Atlantic coast and the wines are more similar to Uruguayan wines than to any Chilean/Pacific counterpart. Their Sauvignon Blanc has more bright and fresh aromatics without being overwhelming or tiring (as so many coastal Sauvignon Blancs can be, in my opinion). I love the impact this has within Argentina. As a country where it is nigh impossible to get imported wines, Costa y Pampa offers a rare chance for sommeliers and wine students to try something from the coast – and I really think that should be celebrated. Trapiche fortunately have the budget and logistics to be able to plant in new territories, but with the success of these wines, I’m sure we’re going to see more coastal vineyards in the not-so-distant future in Argentina.

24hr skin maceration. S.steel tanks.

Alc. 12% pH: 3.36, Total Acidity: 6.06

Residual Sugar: 1.80 g/l

Trapiche: www.trapiche.com.ar

£15, www.enotriacoe.com

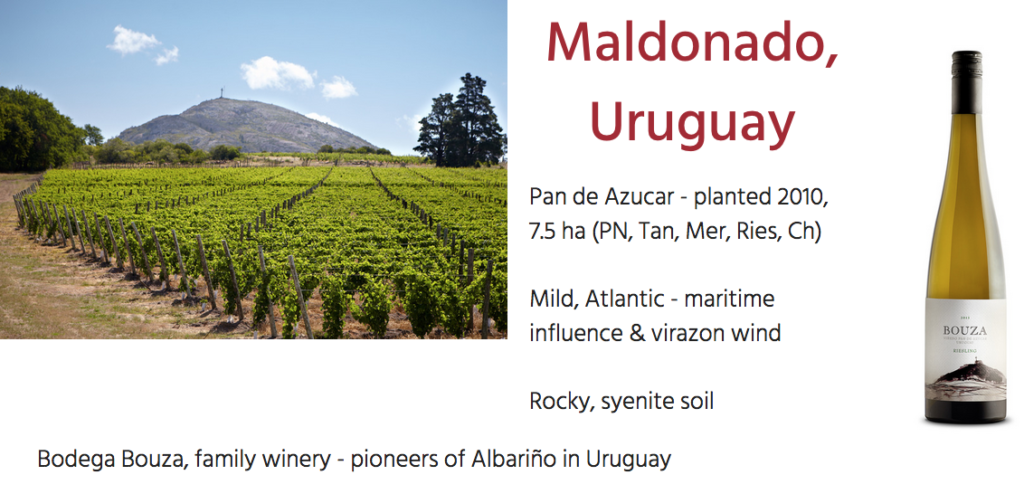

Tara Chardonnay 2015

This is another case of a larger winery, Viña Ventisquero, breaking the rules and creating a boutique project in an off-the-beaten-path area. You can’t get much more off-the-beaten-path than this location: on the edge of the Atacama desert in northern Chile. The Tara vineyard is extreme in terms of soils, in terms of sunshine and in terms of how dry the region is. However the cold Humboldt Current and Pacific Ocean mean that a thick camanchaca coastal fog bathes the vines every morning and keeps the evening temperatures cool so the grapes ripen nicely. This Chardonnay is unfiltered, foot-trodden and made in an artisanal way, which is another reason why it proves an interesting departure from Ventisquero’s usual style. I love the salinity and texture to this wine; it is appetizing and makes me hungry while drinking it!

Foot-crushed (50% whole cluster)

Native yeast, s.steel tanks

Aged 24 months (70% in used oak)

Alc. 13% pH: 3,22 Total: 6.31

Residual Sugar: 1.99 g/l

Viña Ventisquero: www.ventisquero.com/tara/

£37, www.winetreasury.com

Mimo Tinto de Ica 2017

I always knew this would be the wine that would generate the most conversation in the tasting (it’s hard not to with an orange wine, right?). But for me this wine represents something really important happening in South America at the moment – the re-appropriation of old vines and traditional varieties. Quebranta and Torrontes are typically only used for Pisco-production in Peru but winemakers Matias Michelini (from Argentina) and Pepe Moquillaza (from Peru) wanted to make a wine that really embodies the varieties and their potential to make characterful wines. Coming from the coastal region of Ica, these vines are all on their own roots (pie franco) and 30-years-old. The wine reflects the wild landscape, the salinity of the soils and the rusticity of these Criolla varieties. I’m thrilled to see this Peruvian wine with such identity and complexity. If you’ve ever had real Peruvian cuisine, you’ll understand why a true Peruvian wine shouldn’t be any less complex and unique. Go big or go home, I say.

Co-ferment Quebranta & Torrontes.

60 days on skins (33% whole bunch)

6 months neutral oak. Alc. 12.7%

Total Acidity: 6.1 Reducing sugars 3.1g/l

MIMO = Matias MIchelini, Pepe MOquillaza

£23

The Altitude Frontier

Planting at altitude is nothing new in South America. The first vines were planted near Cuzco in Peru 500 years ago… they didn’t survive but altitude plantings in Bolivia (where every vineyard is above 1600m) and Argentina have thrived over the last couple of centuries. While planting at high altitude is traditional, it is also a very new movement too.

Planting at altitude is nothing new in South America. The first vines were planted near Cuzco in Peru 500 years ago… they didn’t survive but altitude plantings in Bolivia (where every vineyard is above 1600m) and Argentina have thrived over the last couple of centuries. While planting at high altitude is traditional, it is also a very new movement too.

Vineyard plantings in Salta have more than doubled in the last 17 years, making Cafayate one of the fastest growing wine regions in Argentina today. And further south in Mendoza we are seeing higher and higher vineyards in the Uco Valley and also in other areas of Mendoza above the city and in Uspallata en-route to Mount Aconcagua. On the other side of the Andes, we are also seeing altitude developments in Chile – notably in Elqui, Limarí and Cachapoal. The climb uphill is not just about cooler temperatures but also about more interesting soils and, of course, the all-important water access.

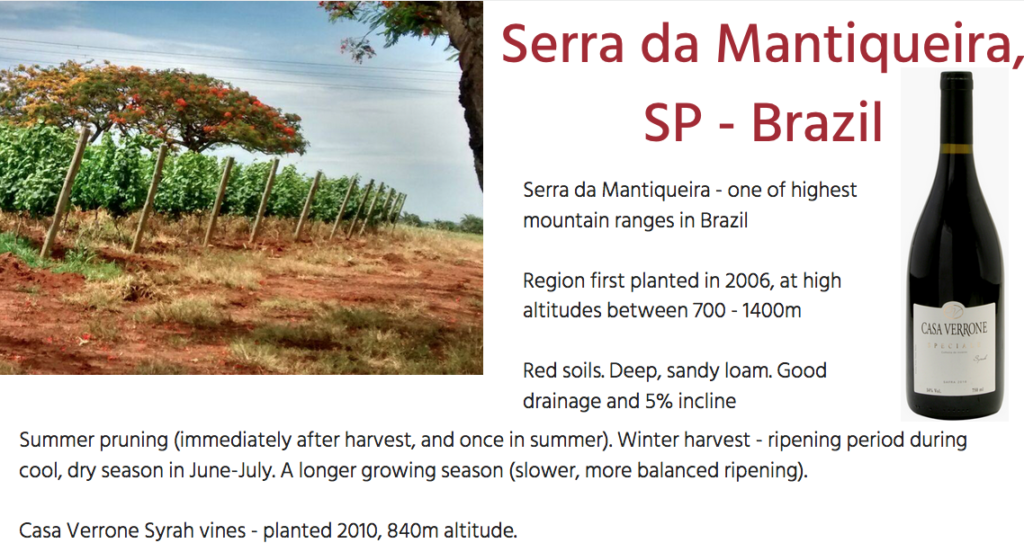

In Brazil and Uruguay, although the mountains are much smaller, there have also been several higher altitude developments, in particular in Brazil, which is why I chose a wine from Serra da Mantiqueira as the first in the tasting.

Casa Verrone, Syrah Speciale 2016

This smaller family producer planted this vineyard in 2010 on one of the highest mountain ranges in Brazil – the Serra da Mantiqueira, in the Sao Paolo region. Altitude is one way of finding cooler temperatures in the sub-tropical climate of Brazil, but what’s also innovative about this wine is the winter harvest technique. Casa Verrone prunes their vines in the summer and allows the fruit to grow in the winter months of June and July when the temperatures are typically much cooler and the skies are sunny and dry. This gives the vines a longer growing season and produces more balanced fruit and I think that is particularly evident in this Syrah, which is fruit-driven but quite juicy and bright.

Winter harvest. 840m altitude.

12 months French oak. Alc. 14%

pH: 3.85, Total Acidity: 3.9

Residual Sugar: 1.3g/l

Casa Veronne, www.casaverrone.com.br

£16. Seeking representation: marcio@casaverrone.com.br

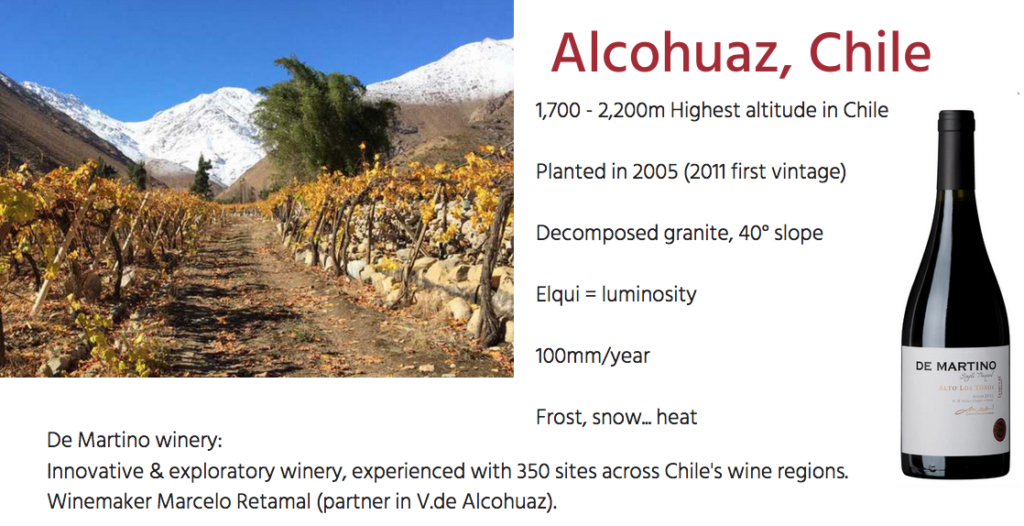

De Martino Alto de Toro Syrah 2011

This is a vineyard I love and have visited several times because it is just so remarkable. The highest altitude vineyard in Chile, the Alcohuaz vineyards sit proud at up to 2200m above sea-level at the end of the Elqui valley. Owned by Viñedos de Alcohuaz, this fruit is purchased by De Martino winery (whose winemaker Marcelo Retamal happens to be co-owner of Viñedos de Alcohuaz) and 2011 was the first commercial vintage from this young vineyard. The wine shows the great intensity of this vineyard – the pure sunlight and luminosity, the cold evenings, the extreme winters and the poor, granite soils. It was such a pleasure to taste this wine with some age on it because it really reveals that it is a remarkable wine from a remarkable location that may well be new, but already has the potential to age. This was another favourite in the tasting.

90% Syrah, 10% Petit Verdot

2 years in foudre

De Martino, www.demartino.cl

£20

www.virginwines.co.uk, www.bbr.com

Where next for South America’s wine regions?

This is something I’m planning to cover in my upcoming guide to South American wine. But, in a nutshell, I think we’re sure to see more developments at altitude, more along the coastline and further penetration of Patagonia for viticulture. The refocus on traditional wine regions and varieties is also something to be followed very closely in South America. There’s an unquenchable thirst for knowledge and experimentation among the current generation of winemakers in South America, which is driving them to push the boundaries more than ever before. And this is why, I believe, that South America is one of the most dynamic wine continents today.

More on South American wine regions

- Wine guide to Argentina

- Wine guide to Chile

- Wine guide to Peru

- Wine guide to Brazil

- Wine guide to Bolivia

- Wine guide to Uruguay