As a journalist visiting wine harvests, I’m pretty used to swanning in and out while others are doing the hard work. While the harvest team are busily picking grapes under the hot sun, I usually just take photos, kick around a few rocks with the viticulturist, squeeze a few grapes, and drink a lot of wine. No wine journalist, if they are being honest, ever does any of the hard grind in the vineyards. And if they do, it is a token gesture before they return to the comfort of their armchair and laptop an hour, a day, or maybe a week, later.

I imagined stomping grapes in the stone lagars of the Douro would be the same. Not quite. Once I had gotten my toes wet in the big pool of purple grapes, the rogador (aka. man in charge) wouldn’t let me out. Not until I had finished my corte – a rhythmic shuffling from one end of the lagar to the other in a line of grape stompers.

Although you might see videos of loud music playing, boisterous boozing and purple parties in the wine pools, the reality of foot treading in the Douro is far from that. This is a job which is done with precision and sobriety. It looks more like the military performing the can-can – without any music, frills or high-kicks. It is a process that can last anywhere between one and three hours, and the rogador said I had to finish the job. Quite rightly so.

The grapes and juice only macerate together in the lagars for less than 48 hours (compared to weeks for conventional red wines), so every grape must be squeezed by foot in order to get the high extraction of colour and flavour they are aiming for and to break up the big, solid cake of grapes.

The grapes and juice only macerate together in the lagars for less than 48 hours (compared to weeks for conventional red wines), so every grape must be squeezed by foot in order to get the high extraction of colour and flavour they are aiming for and to break up the big, solid cake of grapes.

After the corte, when the rodagor decides the grapes have been stomped sufficiently, you are given your liberdade* – your freedom. The mood then lightens, as everyone sings and dances – in an ordered fashion – in a conga line through the grapes to celebrate liberdade and the end of the shift for that night. The process and protocol have remained the same for centuries.

A game of survival

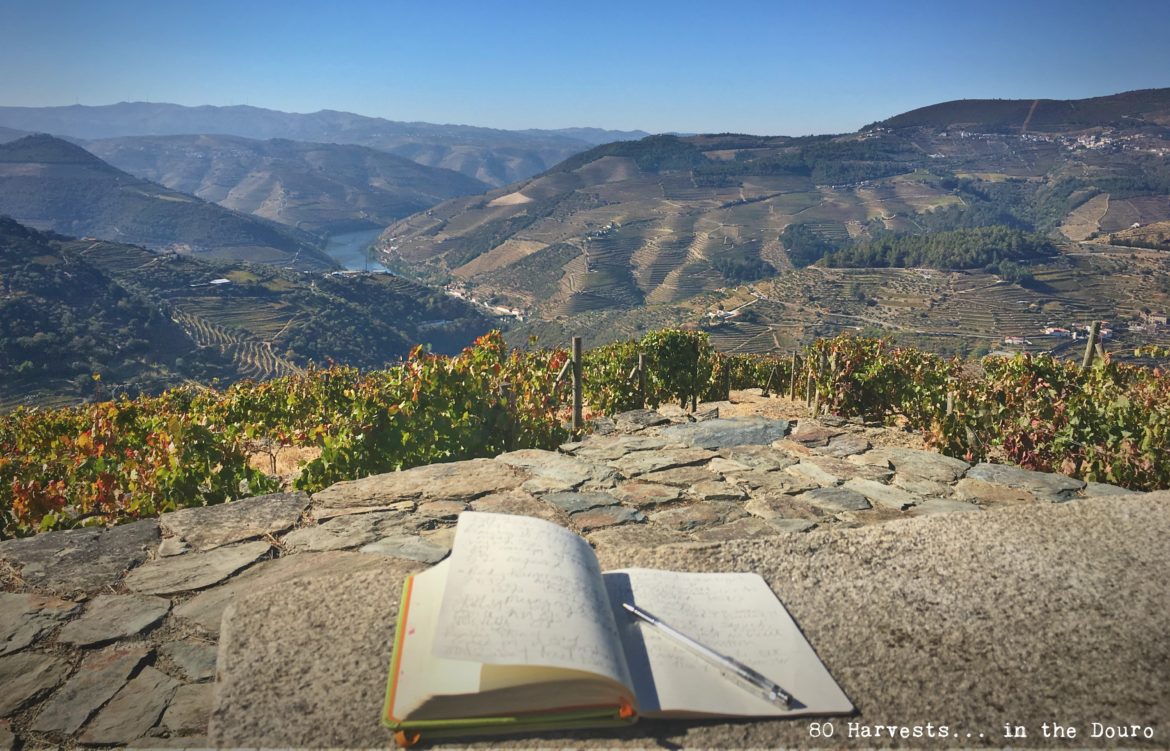

Discipline and a respect for tradition is what keeps Port production unique today, although maintaining these virtues is by no means easy. The Douro is a region with epic stories of boom and bust – hardship seems to be part of the very terroir.

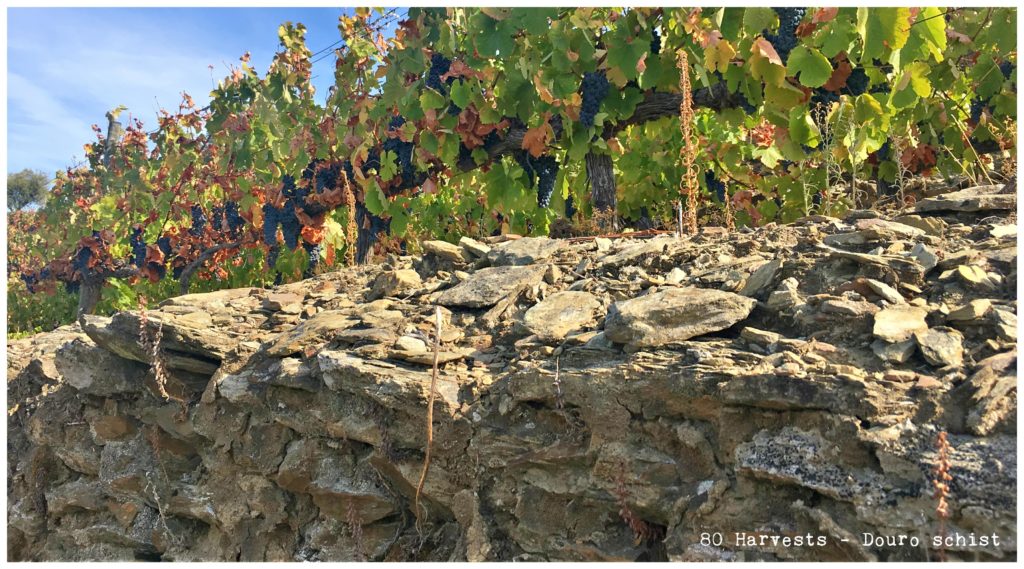

You just have to look up towards the sky to see how much hard work this region is. The vineyards are planted into the steep, schist hillsides, which sometimes reach an incline of 70%. So solid is the bedrock that some producers have had to use dynamite to make a dent big enough to plant a couple rows of vines.

Erosion is also such a risk that the rows traditionally had to be supported by tall retaining walls, socalcos, to keep them from disappearing down the hillsides. It’s an arduous job to build and maintain these walls, however picturesque they look, and the number of locally trained stonemasons is dwindling. Producers would perhaps abandon the socalcos altogether if it weren’t for the subsidies offered by UNESCO, which help producers afford to keep this viticultural patrimony alive.

Thriving in adversity

The rocks may look bare and inhospitable but the vertical cracks in the schist are the key to survival for these unirrigated vines. With an average of just 650mm rainfall a year – which plummets to 380mm in years of drought, like 2017 – the vines have to dig deep to reach water sources. Some of the vine roots can grow over 20 metres deep through the schist.

Grape varieties have to be somewhat hardy to survive the long, dry summers here and the Port varieties have been determined by a process of natural selection over the centuries. Producers in the Douro have also always played the game of numbers in order to make sure they have successful production year after year, and field blends of several varieties offer a wide enough window of ripening times and grape profiles to succeed in making a ripe and robust wine most years.

Although single-variety wines and Ports are an emerging trend in the Douro, the overwhelming majority of wines made there are field blends of five grape varieties. Touriga Nacional offers the depth and volume, Touriga Franca gives the floral perfume, Tinta Roriz adds some flesh, Tinta Barroca aids the sweetness and Tinta Cão brings in the spice. It is easy to isolate the reasons why these grapes are included in the final blend, but the reality is far more Darwinian, a case of survival of the fittest and those that perform best in the harsh conditions.

The terroir has not only shaped the wines in terms of variety, but also in style. The vibrant colour of Port wines and their fullness of flavour come from the particularly thick grape skins, which reduce juice evaporation and protect the grape flesh in the hot and dry climate. (The thickness of the skins is another reason thorough treading is essential.)

The development of Port itself as a category is similarly a story of survival. In a time before air-conditioning existed, the Douro was too hot to store the wines (infamously monikered the ‘Douro bake’). So the wines were shipped downriver to Porto, where the ocean breeze from the Pacific kept temperatures cooler. The beautiful Port houses neatly sitting side by side along the river overlooking the city were for centuries the place of refuge for Port wines to age and develop.

Aided by the port-side location, the wines were easily transported and garnered fans and customers across the globe. Before the wines were shipped from the port to the consumer, they were doused with a healthy pour of distilled spirit to stabilise them and protect them from spoilage while on long – and hot – journeys at sea. As the world acquired a taste for these powerful red wines, high in alcohol and abundant with sweet fruit, the style of Port was forever set in stone as a fortified red wine.

A future of selective tradition

Making great Port isn’t a cheap endeavour. It requires large volumes of wine, lots of manpower and a patience rarely found in our fast-moving world. When I visited the Douro for 80 Harvests, I was fortunate enough to be a guest of one of the great stalwarts of quality Port – Quinta do Noval. Founded in 1715, like many producers in the region, Quinta do Noval has had its share of ups and downs. Although it was known for declaring many great vintages historically, in the 70s and 80s it began to fall on hard times.

But the historic Port house found itself a fairytale ending, when the insurance company AXA bought the property in 1993. Since then, they have been investing in restoring the traditional agricultural and winemaking techniques and they have the long-term vision and financial resources to afford to do so.

“It’s a wonderful situation to be in – having an investor behind you that is willing to give some TLC to one of the great vineyards in the world,” says Christian Seely, who has managed Quinta do Noval’s turnaround since 1993. This included the daunting replanting of 100 hectares: “It looked absolutely terrifying at the time. To see it all torn up without vineyards was rather scary.”

But taking the risk of replanting was worth it because now Quinta do Noval has their vines separated into the different varieties and each planted on the most appropriate parcel depending on soil, slope and sun exposure. And, over 20 years later, the vines of these noble varieties are coming into their sweet spot in terms of productivity and quality.

Another big innovation was bringing all of their production uphill to the Douro valley, in a temperature-controlled winery. However, the rest of their process remains largely traditional (and their vineyard is a pleasing patchwork of socalcos).

Quinta do Noval is one of the few producers that continue to their Ports in lagars: “We’ve made experiments where we have dividing the parcel in two and vinified half of the grapes in lagars and the other half in stainless steel vats,” explains Seely. “You make a very nice Port in a stainless steel vat, but lagars always give the best result. Foot treading is an extremely efficient, mechanical way of treading, it is very gentle but thorough. It’s a very expensive way of making Port but if you want to make something great, I believe that it’s essential.”

Although they also use mechanical feet on occasion (another innovation of theirs), the process remains the same and celebrates the long-running tradition of Douro winemaking. For me, this was evident in tasting the wines.

Good Port can reflect the essence of the Douro and it is an exciting and emotional wine to taste. With each glass you feel the warm black fruit notes from the intensity of that summer’s heat; the heady notes of wild rose and brush herbs that are carried by the afternoon breeze; the textural tension from the vines fighting for survival on poor, schist soils; and the richness and depth artfully achieved by all the legwork that has gone into making this wine. With time, vintage Port gradually unlaces, elegantly revealing its DNA further.

Good Port can reflect the essence of the Douro and it is an exciting and emotional wine to taste. With each glass you feel the warm black fruit notes from the intensity of that summer’s heat; the heady notes of wild rose and brush herbs that are carried by the afternoon breeze; the textural tension from the vines fighting for survival on poor, schist soils; and the richness and depth artfully achieved by all the legwork that has gone into making this wine. With time, vintage Port gradually unlaces, elegantly revealing its DNA further.

It’s a thrilling experience to drink Port wines from decades past and travel back to what was happening at that time. If there ever were a time-capsule wine, Port would be it.

–

–

–

Crushing grapes by foot in the Douro (the first minute)

*Admittedly, my liberdade came earlier than everyone else’s. I only had to do the first corte, which was just over an hour long, while they carried on stomping for another corte of the lagar because the grapes were harder to press this vintage due to thicker skins. I was drinking Port by the time everyone else won their liberdade, in the comfort of an armchair by the lovely fireplace in Quinta do Noval. Cry me a river.

Tasting Notes from Quinta do Noval

Ruby Ports

Noval Black

Noval Black

This is their ‘newest’ Port (although they have been making it for over a decade), being the latest addition to the portfolio as a more affordable, younger Ruby port. The grapes are bought from local growers and fermented in a stainless steel tank, rather than a lagar, which helps achieve the €11 price tag. It has lots of bright and mature fruit notes and an intense sweetness and peppery spice. This is a great intro to Port and works nicely as a cocktail base.

Late Bottled Vintage 2012, Single Vineyard Unfiltered

The grapes for this Port are all from the Noval estate and made in the traditional lagar foot-treading method, which make it a rarity in the LBV world. It has a dark, mature fruit nose with a spicy mouthfeel that has tannin and structure. It’s an excellent value Port that delivers a lot for its €20 price point. Mouthfilling, rich and intense.

Quinta do Noval Vintage 2014

With a long growing season, 2014 was a great vintage for both wine and Port and this really shows the potential. It has a fragrant nose with floral and fruit notes, together with length, finesse and intensity. Quinta do Noval often declare a vintage regardless of what the IDVP declare, and I think they are spot-on with this one.

Quinta do Noval Vintage 2015

There is much more red fruit on the nose for this Port, with heady floral aromas and it is very mouthfilling and intense. This is a vintage that was declared by the IDVP and it was a bumper vintage for the region because even though the summer was hot, the winter rains gave enough water to the vines to survive. The resulting Port is vibrant and voluptuous.

Vintage 2003

An intense vintage Port with a dense berry nose filled with ripe blackberries, dates, black cherries and plums. Notes of chocolate add depth, while floral notes add some height and the mouthfeel is lush and full-bodied with smooth tannins and a long finish. Delicious.

Nacional 2003

The Nacional is much darker than its Vintage sibling. Although they are from the same vintage, this smaller area of old vines produces a very different profile of Port – sumptuous yet refined. It feels much younger in the glass and the fruit is less boastful but underpins the wine alongside very attractive floral and liquorice notes. Silky tannins and excellent length. You couldn’t ask for more.

Tawny Ports

Quinta do Noval 10 year old Tawny

Already going amber in colour, the house style of Noval’s tawny shows more development than many of its competitors of the same age. This Port has a nose of nuts and fig jam, with a marzipan and red fruit mouth that reminds me of a freshly-baked Bakewell tart.

Quinta do Noval 20 year old Tawny

A burnt caramel colour, this 20 year Tawny has an abundance of dried fruit, nuts and dried flower notes. It is rich and sweet and has outstanding length. This is an excellent Tawny with complexity but very appetising flavours and aromas that beg you to have another glass.

Quinta do Noval 40 year old Tawny

There is no 30 year old Tawny, basically because Noval don’t have the stock, but this also means that you can see a remarkable difference between the 20 year version and this 40 year-old. The nose has a mille-feuille of almonds, vanilla beans and marmalade, and the mouth is intensely sweet with a rolling complexity and long finish. This is the sort of Port you can taste upstairs and by the time you are downstairs, through the front door and getting into your car you still have the taste lingering in your mouth.

Colheita 2003

This was a hot year for all of Europe, and even more so in the Douro, but the Port varieties are capable of handling the heat and this Tawny has an open nature with notes of toasted nuts, soaked sultanas and candied orange peel.

Colheita 1964

This old vintage tawny is sweet, intense and dense with aromas of bitter orange, almond, and marmalade. There is an intense sweetness and a never-ending finish that slowly unfolds and lingers. If I had made it into the car for the 40 year old, this 1964 is still lingering by the time I’ve arrived at Pinhão village. An absolute treasure.

Quinta do Noval Wines

Noval started to make red wine (unfortified) in 2004 and today it produces a handful of wines:

Cedro do Noval 2016

A blend of Gouveio and Viosinho, this white DOC wine comes from the very top of the estate where the altitude keeps the vines cooler and you can make this fresh white wine. It has a distinct character with crushed almond notes, citrus rind and a finish that achieves both a steely freshness and a creamy complexity (thanks to its 20% barrel fermentation).

Cedro do Noval 2014

This is their blend of 35% Touriga Nacional, 30% Syrah, 20% Touriga Franca and 15% Tinta Roriz (Tempranillo), which spends some time in oak but is very much dominated by red fruit notes and mature, fine tannins following a long growing season. The addition of Syrah means it cannot be labelled with the DOC.

Quinta do Noval, Touriga Nacional 2014

The Douro is the home of blends but this is part of their single variety series highlighting the Queen of the Douro’s red varieties – Touriga Nacional. With the typical notes of lavender, dried rose petals and black fruits on the nose, the mouth is elegant with a lingering ash and graphite note on the finish. It is a dark wine but has femininity and freshness. Having tried the 2009 vintage, I can confirm that this is a wine that ages well.

Quinta do Noval Douro DOC 2014

A blend of the typical Port varieties, this has a much darker fruit character and more structured tannins, making this a real food wine that would stand out with rich game dishes. The addition of Tinta Cão in this gives it spine, which is fleshed out with Touriga Nacional and Touriga Franca.