If you are studying for your WSET or sommelier exams, the Champagne process can seem a bewildering concept with lots of rules to learn. The CIVC (Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne) has quite rigorous regulations in terms of harvest times, yields and pressing, but the chef de cave, or cellar master, has several key moments in which they can choose to completely change the style of Champagne. The variety found within Champagne is quite outstanding, so I’ve detailed the different decision-making moments in the Champagne process that ultimately change what ends up in your glass. This falls into our Fast Facts section, but being Champagne – it isn’t fast at all… Grab a cup of coffee or, better yet, a glass of Champagne:

Champagne process: The vineyard & harvest

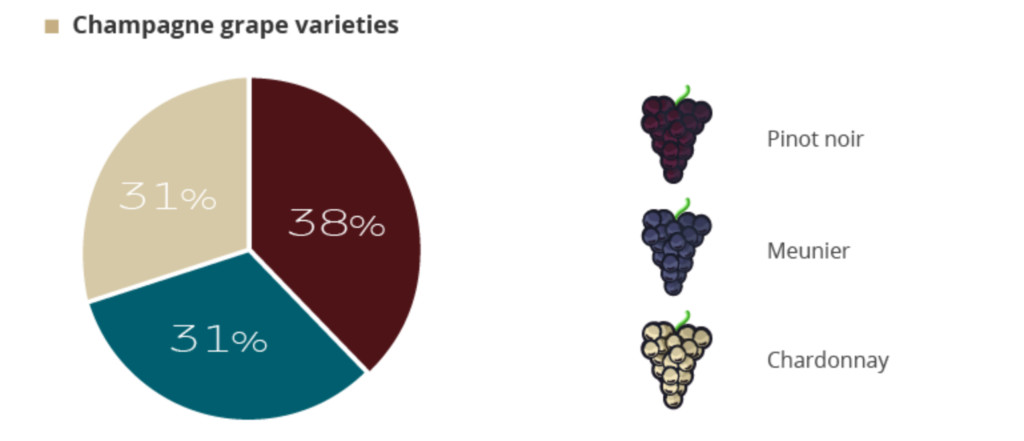

The first step in the Champagne process is based in the vineyards – what grape varieties you have and where. This is normally not a decision the grower or the producer makes; it is usually down to what they have inherited or have available. Champagne is a highly-sought-after region with very little land available to purchase and it has already been planted to full capacity (as defined by the CIVC), so there’s little wiggle room. The long-awaited expansion of the region, which would include 40 additional villages, is still in the pipeline so for now it is only the chef de cave of large houses or négociants (see glossary below) who will have a significant choice in which grapes to buy for their next vintage. The region you buy from will dictate what raw material you have:

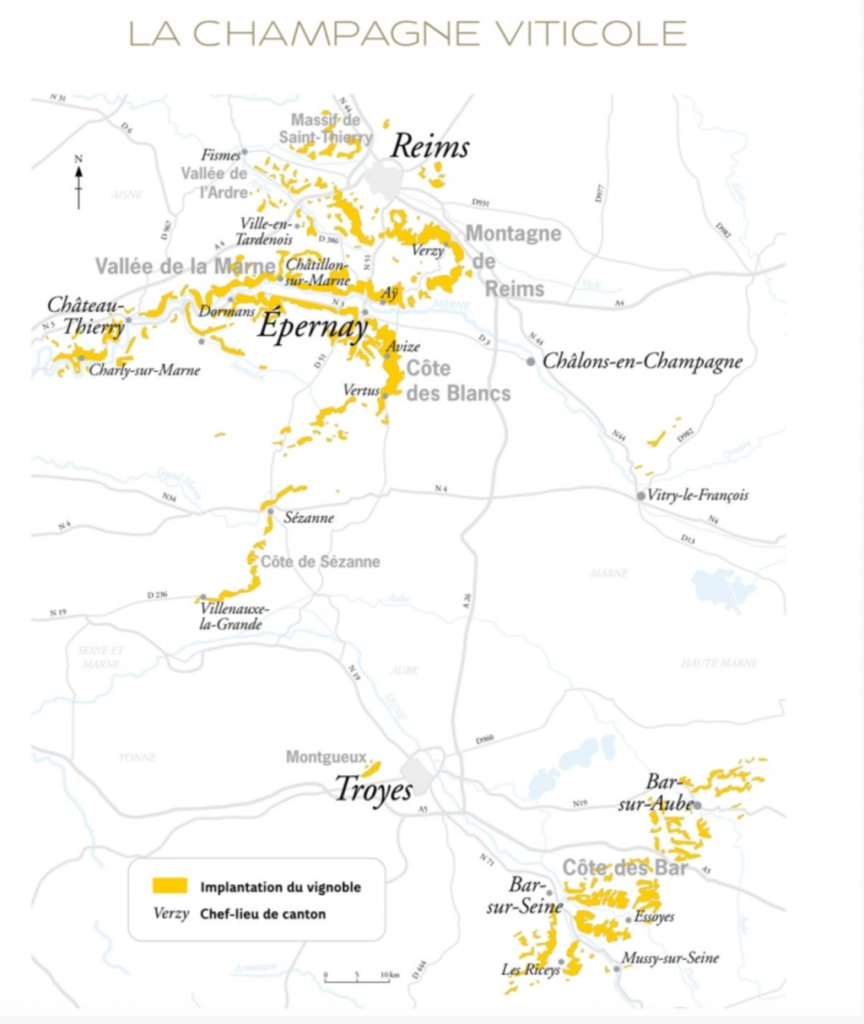

Champagne wine regions

There are some broad generalisations that can be made about the wine regions of Champagne. However within each village (there are over 300 of them) there are several differences which also impact the grape variety and character of the wine.

Champagne is delineated into two areas:

- Aire délimitée – A widespread area where Champagne can be made, vinified and produced. There are 634 villages within the production area.

- Aire production – A smaller area within the aire délimitée where grapes used for Champagne are grown. There are 318 villages permitted to grow Champagne grapes.

All of Champagne has a cool, continental climate. While it isn’t as extremely continental as Burgundy, for example, frosts and winter freeze (like in 1985) are a risk. The most persistent threat though is rot from humidity. The altitude of vineyards range between 90m and 300m above sea level, and the slopes can range from 12% to 60% incline.

Then there are broad regional appellations (such as Côte des Blancs for example), which have several villages and different sites within them (such as Avize). But within those villages – whether they are non-cru, Premier Cru (44 villages) or Grand Cru (17 villages) – there is a wide range of sites, which means the quality can vary greatly. This is seen as a bit of a shortfall of the appellation system, which doesn’t yet separate quality of sites within the villages. For example, while one village might all be considered Grand Cru – and labelled and sold that way – the most valued vineyards are on the mid-slope where there is a greater concentration of chalk, a good aspect and exposure to the sun, and good drainage. The top of the slope usually has sandier soils and tends to be more water-logged due to its proximity to the forest, and the bottom of the slope enters the frost-risk zone, so it is more likely planted with later-budding Pinot Meuniere. This all means that knowing your individual lot is essential and fortunately, after centuries of highly documented viticulture and winemaking in Champagne, most chefs de cave inherit a detailed guidebook from their predecessors, as Jean Baptiste explains in this interview online. That being said, here is a general guide to the regional differences:

Montagne de Reims: Land of Pinot Noir

South- and north-facing slopes mainly dedicated to the production of Pinot Noir, although both offer a different character – the north-facing slopes (including Verzenay and Mailly) are much cooler and so offer higher levels of acid and delicate aromas; and the south-facing slopes (like Bouzy and Ambonnay) are warmer and produce more powerful wines with more body and fruit character. 82 different Pinot Noir clones also mean there is quite a fair bit of variety in the region. Home to 10 of the 17 Grand Cru villages, and many Premier Cru villages.

Côte des Blancs: The sweet spot for Chardonnay

Blanc is the clue here – white soils (chalk) and white grapes (over 95% of vines planted are Chardonnay). The mainly east-facing slopes in the region offer some protection from wind and rain – aided by the forest at the top – and so the more delicate variety of Chardonnay works well here, whereas Pinot Noir wouldn’t necessarily ripen. Cramant, Avize, Oger, Le Mesnil-sur-Oger, Oiry and Chouilly are all Grand Cru (6 out of the 17 in Champagne) and the rest are Premier Cru.

Vallée de la Marne: Where Pinot Meuniere survives, and thrives

With mainly south-facing slopes, the region is known for its red varieties – Pinot Noir and Pinot Meuniere. There is, however, a problem in Marne; it is low-lying and so frost is a risk. This is why it is more widely planted (especially on the cooler north-facing slopes) with Pinot Meuniere, which is a later budding, earlier-ripening variety and thus less vulnerable to frost attacks.

Côte de Sézanne: Chardonnay heartland

While the Côte des Blancs is most renowned for its mineral-driven Chardonnay style, the Côte de Sézanne is best known for its more aromatic, tropical style of Chardonnay. There is a bedrock of chalk in Sézanne but it is mixed with a topsoil more dominated by marl, sand and clay. Over 70% of the vineyards here are Chardonnay.

Côte des Bar (the Aube): The outsider

There’s some controversy surrounding this area’s inclusion in Champagne, as it is over 150 km further south than the other main Champagne regions. It is warmer in the summer and ripens Pinot Noir more easily so the fruit-forward grapes from the Aube are used in many ways as a Plan B or non-vintage wines (the Aube supplies 40% of Champagne’s Pinot Noir). This area of clay-based soils may not be as highly revered as the traditional wine regions (above) but it is more reliable year-on-year.

Yield and viticulture choices

The INAO caps the legal limit for the Champagne yield at 15,500 kg/ha for AOC production and each year defines a new maximum yield – depending on the vintage conditions and the supply/demand balance of the market. Although most of the time producers are far below this limit. Vines are planted at high density in Champagne (8,000 vines per hectare). The majority (over 80%) of vines are grafted onto the lime-tolerant 41B rootstock, which can tolerate the high chalk content of the soils.

Harvest

The harvest date is also limited by a governing body, the AVC, following a consultation with the different growers and producers who frequently monitor the ripening and the acid and sugar levels in the vineyards. Harvest cannot start before the grapes have a minimum potential alcohol of 9% abv, but again this minimum potential alcohol changes depending on the year.

Training and pruning are limited to four systems: Taille Chablis; Cordon de Royat; Guyot (single and double); and Vallée de la Marne (for Pinot Meuniere). Most of the pruning systems retain lots of old wood, which helps build resistance to frost.

Harvesting in Champagne is all done by hand because you need to press the grapes in whole bunches (and no machine can pick whole bunches). It is usually a fast and furious process as the producers try to get all their grapes in before the rain or any grey rot sets in. It is only in about 3 vintages out of every 10 that the weather will stay fine and picking can be done at a more leisurely pace.

Champagne process: Pressing

Pressing of the grapes is highly monitored in Champagne, as this is where you take a significant step in the quality of the juice obtained, which has a great effect on the Champagne process. Pressing techniques are very gentle in order to extract the juice from the pulp without crushing the seeds or breaking the skins, both of which release bitter phenolics and tannins which will impact the final wine.

You can legally only press 102 litres of must per 160 kg of grapes and each producer must weigh their grapes as they come in and the juice from the press to prove that they are within the legal limit.

The goal is to press as soon as you can after the harvest in order to avoid oxidation or losing any juice from the grapes. Growers and producers who have their vineyards close to the winery will press in the winery. However larger houses will have press houses within the vineyards in order to press there. The juice (must) is then transported to the winery.

Traditional vs. Pneumatic press

There are two types of press used in Champagne: the vertical basket press and the pneumatic press. Both take around 4 hours to press a marc (4,000kg, the traditional unit of measurement for a press-load) of grapes.

The vertical basket press offers a more gentle process. However it requires more work to load, unload and do the retrousse (shovelling all the grapes back in the middle for another press). Producers in particular like to use this press for the red grapes, as it doesn’t allow much extraction of bitter phenolics or tannins (which are naturally more abundant in red grapes).

The pneumatic balloon press is also a gentle press, but somewhat less gentle than the vertical basket press. It is, however, quicker and only one person is needed to operate the machine during the pressing, rather than the several needed for the vertical press. This press is particularly popular for white varieties, because you don’t need to be as careful about breaking the skins because there is less colour and tannin extraction. In fact, some producers prefer to add some of the phenolics to give more texture to Chardonnay.

Separating the cuvée from the taille and rebêche

Only 80% of the juice can be called the cuvée (20.5hl of a 4,000kg marc), the rest has to be considered the taille (5hl of a 4,000kg marc). Usually the first juice coming from the press goes to the taille (because it might have earth particles or be more oxidated). Then when you start pressing the grapes, you get the purest part of the pulp – the fine quality juice which is rich in sugar and acid (both tartaric and malic). This is the cuvée and is prized as the best with the most finesse and subtle aromas. The middle press is considered the very best, and is called the heart of the cuvée (Coeur de Cuvée).

The last juice from the press now comes from areas in greater contact with the skins and seeds and this is categorised as the taille. It also has high sugar but much lower acidity and might have higher colour concentration. The taille is often added to the final wine for roundness and fruity character but is not used in the very top Champagnes which are destined to age a long time. Each year, no matter how great the vintage, producers must reserve a minimum of 20% of their production to be stored as reserve wine.

Following the press, most producers will leave the fresh grape juice to settle, known as débourbage. After 12 to 24 hours, the wine is racked and the sludge at the bottom is sent for distillation too.

Champagne process: Primary Fermentation

Before fermentation, producers make the choice to add sugar (chaptalisation) if needed and whether to inoculate with yeast. Some producers choose to have natural ferments using native, ambient yeasts. However the majority of producers will inoculate either with commercial yeasts (usually using very neutral yeasts, so neutral and distinct that they are known worldwide as Champagne yeasts) or with a Pied de Cuve (yeasts cultivated from the skins of grapes from your own vineyard picked a week or so before the harvest).

A chef de cave will also make an important decision on whether to ferment in oak or stainless steel and how oxidative they want their fermentation to be.

The other significant fermentation in the Champagne process is the malolactic fermentation (transforming the tart, malic acid into softer, lactic acid). This choice is usually down to the vintage – if the year was particularly warm and there was good ripening, then a chef de caves might choose not to do any malolactic fermentation at all, and vice versa on a wet, cold year where acids will be particularly high).

Champagne process: Base wine & ageing

Once they have the base wine now the chef de caves makes the decision as to whether they want to age that base wine on the lees or filter and/or fine the wine now. This depends on what style of Champagne he/she is planning to make. Some winemakers will keep this base wine on the lees for a long period in order to allow some autolysis to happen at this stage, while others will filter right away.

Reserve wines are kept back for several vintages in order to blend into non-vintage Champagnes, to give some consistency to the rather wide vintage variation that you get in Champagne. The reserve wine might be kept separately or you may already blend it with previous vintages (which producers confusingly shares a name with the very different ageing process used in Sherry-making, the solera system). You might also choose to age your base wine in oak at this stage. Either way, you keep your base wine as a still wine until you are ready to transform it into Champagne…

Champagne process: Secondary Fermentation in bottle

The most famous part of the Champagne process is what makes it sparkle – the secondary fermentation in bottle. A process discovered by accident as bottles of wine refermented in the boat journey from France to England, it has been replicated intentionally ever since the 18th century (although Champagne as a region has been making wine for far longer – since the 900s).

In order to make Champagne pop, the process is all done within the bottle: the base wine is filled into the bottle and the liqueur de tirage is added. The base wine at this stage has almost no sugar or yeast left (as the yeast and sugars have all been used and converted to alcohol in the first fermentation) so the liqueur de tirage – a mixture with sugar and yeast – is essential. Cane or beet sugar (20-24 g/l is used to create a pressure of 5-6 atm, and 1.2% abv approx.)

The conversion into sparkling wine is one of the main goals of the second fermentation and takes around 2 to 3 months. However, there is another goal which takes place over the following months and years until disgorgment. Autolysis is the process which makes Champagne taste like, well, Champagne – those lovely nutty, brioche, toast aromas all come from the destruction of the yeast cells in a process which releases amino acids, proteins and volatile compounds that create this unique flavour and aroma profile. This might start to take place after the first fermentation in the ageing period, but happens – more importantly – at this stage too.

The amount of yeast you add and the period of time you leave the yeast in the bottle (anywhere between one year and in some cases 50 years) will alter the extent of autolysis and the final flavours in the wine; this is a stylistic decision. If you are planning a shorter bottle-ageing period, such as for non-vintage Champagne (minimum 15 months), but still want that yeasty flavour, you will often add a greater amount of yeast in order to accelerate the autolysis effect and final aromas and taste of the wine. Vintage wine has to have a minimum of 36 months, but will often be left for much longer, and so has a more developed yeasty character.

The other important decision the chef de caves makes here is whether he/she will bottle under cork or cap closure for this period. The cork and the cap* make a big difference to the oxygen ingress at this point, which will affect the final flavours. (*With a cap you can choose the amount of oxygen ingress desired.) The more oxidative style will result in nuttier aromas, whereas less oxidative closures will maintain the fresh fruit aromas.

The bottles will either be hand-riddled or turned by a gyropalette during this process. This is more of a philosophical decision, as there is no measured difference between the overall effect after the process. Hand riddling might be cheaper than investing in gyropalettes for smaller producers, and the romance and patrimony of hand riddling is often maintained for special bottles or larger format bottles.

Champagne process: Disgorge and dosage

Producers might choose to keep their champagne in the bottle on the lees in a horizontal position, which will increase the oxygen exchange, or in a vertical position (sur pointe), which will inhibit further autolysis and oxygen exchange.

Once they are ready to disgorge (remove the dead yeast cells) they will now make the decision whether they want to do that oxidatively (leaving a gap of oxygen in the head space) or limiting oxygen in the bottle by jetting (spurting a bit of wine into the bottle to cause the foam to rise and prevent any oxygen being stored in the head space before closure).

The dosage is the last choice in the Champagne process that will dramatically change the style of the wine. The dosage is the amount of sugar, or sweetness, you add to the final wine. After the second fermentation in bottle the Champagne will, once again, be almost bone dry, as the yeast has eaten all the sugar to turn it into carbon dioxide and alcohol. You can, of course, disgorge it like this and sell the Champagne with no added sugar – this type of Champagne is called zero dosage, or Brut Nature.

Brut Nature Champagne is a growing trend (and one I love) but the overwhelming majority add a bit of sweetness with their liqueur d’expédition. The liqueur d’expédition is the winemakers’ last tool to impact the style and the final choice in the Champagne process. A sugary, sweet mixture made with either cane sugar (the most neutral), beet sugar or RCGM (rectified concentrated grape must), mixed with reserve wine (older Champagne base wine), it determines how sweet the final Champagne is and can affect the flavour and aromas.

Dosage liqueur generally contains 500-750 grams of sugar per litre. The quantity added varies according to the style of Champagne:

- doux more than 50 grams of sugar per litre

- demi-sec 32-50 grams of sugar per litre

- sec 17-32 grams of sugar per litre

- extra dry 12-17 grams of sugar per litre

- brut less than 12 grams of sugar per litre

- extra brut 0-6 grams of sugar per litre

- “Brut nature“, “pas dosé” or “dosage zéro” contains zero dosage and less than 3 grams of sugar per litre

Interestingly in Champagne you don’t need a minimum sweetness to call your wine any of these categories, so technically a chef de cave could only add 3g/l sugar and still call their wine Brut. It is quite common for a Champagne house to stick to the same name ‘Brut’ or ‘Extra Brut’ for marketing purposes and adjust the dosage level depending on the character of the harvest. For example, a wine from a high acidity year might have more sugar added to it than that from a low acidity year, but they will be labelled exactly the same.

Champagne process: The different styles of Champagne

I was amazed at the great diversity within Champagne. Perhaps because studying the regulations seems so limiting, I wrongly assumed all Champagnes tasted pretty similar… how wrong could I be? Here’s a guideline to the different styles, but within these each village, each soil, each grape variety and each producer leads to a different style.

Champagne Rosé

Rosé Champagne gets its colour from one of two main methods: Saignée, which is where you bleed off the juice after limited contact with the skins; or a Champagne blend (Rosé d’Assemblage) where you add some red wine to a white (blanc de blanc or blanc de noirs) wine. These can range from just a hint of pink through to a bright cherry-coloured, full bodied sparkling rosé. I had a lovely saignée with steak in Champagne; it worked.

Vintage Champagne

From one single vintage, usually a very good one. Vintage has to be aged a minimum of 36 months in the bottle, and is equally likely to be a blend of the main Champagne varieties or made from a single variety.

Non-vintage Champagne

This is a blend of different vintages, usually with one vintage as the base wine (30% – 60%) and the rest made up of reserve wines (3 – 10 years old). NV Champagne has to spend a minimum of 15 months on the lees and can be a blend of any of the Champagne grape varieties. This is the bread and butter of Champagne production.

Blanc de Blancs Champagne

Made with white grapes – 99% of the time it will be Chardonnay, however Arbanne, Petit Meslier, Pinot Blanc and Pinot Gris are also permitted in Champagne.

Blanc de Noirs Champagne

A white wine made from black grapes (Pinot Noir and Pinot Meuniere).

Recently Disgorged, or Late Disgorged or Dégorgement Tardif, Champagne

This is used to show extended lees ageing in the Champagne process, as the bottle has just been disgorged – the dead yeast cells removed – before releasing. This gives it more pronounced and complex flavours. Some examples include Bollinger’s RD, Veuve Clicquot’s Cave Privée, Krug’s Collection and Dom Pérignon’s Oenothèque.

Prestige Cuvée

When a producer refers to their prestige Champagne, it usually means their very best.

Assemblage

Blend. This can be used to talk about a blend of different grape varieties or the blend of different base/reserve wines. This process is what the chef de cave specialises in.

Estate-Bottled Champagne

Champagne grown, produced and bottled by the same company. This is a common term for grower-producers and houses who own their own vineyard estates.

Champagne – A business

There are many business structures to get your head around in Champagne. There are over 16,000 growers in Champagne, 100 co-operatives, some 320 houses and a handful of associations that control the production. Here’s a glossary of Champagne terms and structures:

Champagne Cooperative

Négociant, or Négociant-Manipulant (NM)

Champagne producer that purchases grapes from other growers but bottles and sells the champagne under their own label. This is a common structure in Champagne and many famous houses function this way.

Grower, or Récoltant manipulant (RM)

A grower who makes and markets Champagne under their own label, from grapes exclusively sourced from their own vineyards and processed on their own premises.

Société de Récoltants (SR)

A family firm of growers (2 or more) who make and market Champagne together under one label, using grapes sourced from family vineyards.

Champagne Broker, or Négociant distributeur (ND)

A distributor who buys in finished bottles of Champagne, and sells them under their own label.

Marque d’Acheteur (MA)

An ‘own brand’ wine label produced exclusively for one client (usually owned by a supermarket, restaurant chain or celebrity).

CIVC

The Comité Interprofessionnel du vin de Champagne is governed by two Chairmen (one representing the Champagne houses, and one representing the Champagne growers). The decision-making body is made up by the Syndicat des Vignerons de Champagne, the Fédération des Coopératives Vinicoles de Champagne and the Union des Maisons de Champagne. It is involved in innovation (research, viticulture, sustainability), marketing (international promotion) and protection (of the name/branding, and quality standards) of Champagne. The committee regulates: yield – dependent on vintage; minimum potential alcohol of the must; maximum chaptalisation permitted; picking dates for each vintage, and each village. For every bottle of Champagne sold, roughly 7 cents goes towards funding the CIVC.

Fast Facts Champagne

- Surfaces under vine: 34,145 ha

- Surfaces in production: 33,765 ha

- 15,800 Winegrowers (less than a third sell under their own brand)

- 140 co-operatives (less than a third make and sell their own branded-wines)

- 300 Champagne Houses

- Annual turnover of Champagne: €4.7 billion

- Biggest export market by volume: UK

- Biggest export market by value: USA

- Domestic consumption: 50%

Did you find this guide to the Champagne process useful? If so, become a subscriber and you can see other regional guides to different wine regions around the world. Join the community at 80 Harvests!

…

[mepr-group-price-boxes group_id=”2070″]