[mepr-hide if=”rule: 2080″]

…

This content is exclusive for Members. Take a look at the introductory packages below to become a Member of 80 Harvests and get unrestricted access to all our content.

Thank you for supporting the journey and being part of the 80 Harvests community!

[mepr-group-price-boxes group_id=”2070″]

[/mepr-hide]

[mepr-show if=”rule: 2080″]

The multilingual vocabulary of wine can often feel like a mouthful, but the pop of a cork transcends all language barriers. There are few other sounds in the world quite so synonymous with celebration. Whether you are opening a fine bottle of wine, a well-aged Port or even a cheap bottle of fizz, that pop announces the party.

Cork has been used as a stopper since the ancient Greeks but it wasn’t until the 17th-century, and the advent of glass bottles, that cork became the standard wine seal.

Watertight, sustainable and good for colour stabilisation are some of the advantages of cork closures as well as its breathable nature which allows the wine to develop over time with a small oxygen ingress. It was the best – and practically only – option for centuries, providing over 95% of wine closures at its peak in the late 20th century. Today cork is used for over 70% of closures and more than 12 billion cork stoppers are produced each year, mainly from cork forests in Portugal and Spain.

Watertight, sustainable and good for colour stabilisation are some of the advantages of cork closures as well as its breathable nature which allows the wine to develop over time with a small oxygen ingress. It was the best – and practically only – option for centuries, providing over 95% of wine closures at its peak in the late 20th century. Today cork is used for over 70% of closures and more than 12 billion cork stoppers are produced each year, mainly from cork forests in Portugal and Spain.

It’s long employment in the wine industry has been extolled by legendary findings of wine bottles under cork which have survived centuries in dusty cellars keeping the wine in pristine condition. Cork was even able to preserve 70 bottles of Veuve Clicquot champagne that had been shipwrecked and submerged in the sea for 170 years.

However there is a downside to cork – and that is 2.4.6-trichloroanisole. TCA for short, or simply described as ‘corked’. TCA is a volatile compound which causes cork taint and contaminates wines with an off-putting smell resembling musty cupboards or wet cardboard.

The TCA level may be minute, but just 6ng per litre – the equivalent of one drop in 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools – can ruin a wine. TCA contamination can come from storing a bottle in a contaminated environment (whether that’s the winery’s fault or storage unit’s), but it can also occur in natural cork.

The level of TCA – or cork taint – in bottles grew so high and the deception so great that in the early 2000s Australia and New Zealand all but abandoned cork in favour of screw caps and alternative closures. Winemakers claimed they were getting stiffed with a much higher rate of cork taint than other wine producing countries, and while evidence was only anecdotal, it was enough to convince over 90% of New Zealand’s wine industry, and 70% of Australia’s, to boycott cork altogether.

“We went through a period in the late 90’s and early 2000’s where there were many examples of badly TCA affected parcels of cork,” explains Australian winemaker for Ten Minutes by Tractor, Sandro Mosele. “There were parcels which were in excess 50%! I have not heard of such crazy numbers in recent times, nevertheless, TCA affected bottles still do occur. It would be very unlikely that we would consider future bottlings under cork… we use the most predictable closure which, until this point, is screwcap.”

The cork industry was not, however, going to give up that easily. The world’s largest cork producer Amorim is now on a mission to obliterate TCA in corks by 2020, and its competitors are following suit.

The success of Amorim and other cork producers will not only be measured by their ability to assure TCA-free corks, but will also be highly dependent on the rise and fall of other closures.

While the cork industry has been struggling to remove the bad taste left by the ill side effects of TCA, alternative wine closures began to spawn. But are there any other closures that measure up to the virtues of cork?

In Australia, following the cork scandal, the main replacement was metal screw caps that twisted onto the bottle neck. Screw caps are airtight, watertight, TCA-free and they cost around $0.12 cents per unit, compared to a good quality natural cork which would set a producer back around $0.50. The downside is that they can have a reductive effect on the wine, and don’t give it the same extent of evolution over time through oxygen ingress. Although for some producers – and wine styles – this more consistent, and lower, rate of oxidation is actually an advantage.

In Australia, following the cork scandal, the main replacement was metal screw caps that twisted onto the bottle neck. Screw caps are airtight, watertight, TCA-free and they cost around $0.12 cents per unit, compared to a good quality natural cork which would set a producer back around $0.50. The downside is that they can have a reductive effect on the wine, and don’t give it the same extent of evolution over time through oxygen ingress. Although for some producers – and wine styles – this more consistent, and lower, rate of oxidation is actually an advantage.

“I use screw caps on Casillero del Diablo wines [$7 – $13 per bottle] because they are reliable with no risk of getting a corked bottle, they are easy to use and good for wines that are ready to drink today,” says Marcelo Papa, winemaker at Concha y Toro, which produces over 13 million cases of wine each year. “However for Marques de Casa Concha [$15 – $20 per bottle] I like natural cork because of the evolution it gives to a good wine. But I’m still very frustrated when I find a corked bottle!”

Synthetic corks, made from manmade materials, are another alternative which claim around 8% of the market including brands like Nomacorc. They are great for marketing as they come in a range of colours but tend to have a cheaper look which is off-putting to the premium segment. The other big negative is that synthetic corks can also have an oxidative effect and pick up TCA contamination from the external environment. The quality of synthetic cork varies greatly though, and they can cost anywhere between $0.09 and $0.32.

Synthetic corks, made from manmade materials, are another alternative which claim around 8% of the market including brands like Nomacorc. They are great for marketing as they come in a range of colours but tend to have a cheaper look which is off-putting to the premium segment. The other big negative is that synthetic corks can also have an oxidative effect and pick up TCA contamination from the external environment. The quality of synthetic cork varies greatly though, and they can cost anywhere between $0.09 and $0.32.

The technical cork – like Diam – is one of the most popular alternative bottle stoppers at the top end of the market. Made from pieces of natural cork fused together, the great benefit of Diam is that a CO2 treatment process eliminates volatile molecules which might lead to TCA. Diam now produces over 1.25 billion technical corks, a rapid growth considering they launched their first technical cork just 12 years ago.

The technical cork – like Diam – is one of the most popular alternative bottle stoppers at the top end of the market. Made from pieces of natural cork fused together, the great benefit of Diam is that a CO2 treatment process eliminates volatile molecules which might lead to TCA. Diam now produces over 1.25 billion technical corks, a rapid growth considering they launched their first technical cork just 12 years ago.

A downside though is the relatively high price (Diam 10 costs around $0.28) and the cheaper appearance. Nevertheless technical corks are a popular alternative for premium, age-worthy wines especially in the sparkling wine industry where TCA is particularly perceptible but ageability is essential.

“The only quality options for sparkling wine are cork or cork-based products such as Diam,” says Emma Rica, head winemaker of a premium sparkling wine producer in England, Hattingley Valley. “We use Diam closures on all our wines for consistency and their reliability for no TCA.”

Then there’s a host of lesser-adopted, but no less impacting, stoppers: the reusable glass Vinolok and the resealable, twisty Helix cork are just a couple. Each have their own pros and cons, but none have yet surpassed the use of traditional wine corks which still lead in the industry. And the leading cork producer, Amorim, hopes that their ambitious plan to completely remove TCA risk in corks will keep it that way.

“We had 10 to 20 really difficult years, where everyone said the cork industry would end,” admits CEO Antonio Amorim. “Screw caps shook the status quo of the industry, but we decided to stay in cork because the room for improvement was enormous. The focus of our research and development has been on TCA, and we will totally eliminate TCA in corks by 2020.”

Considering Amorim have already brought down their TCA screening levels from 10ng/l in 2008 to just 0.5ng/l in 2015 (considered undetectable by the Australian Wine Research Institute), the goal seems feasible. Amorim have in fact already developed a TCA-free technical cork through their NDTech range which has been achieved through several innovations in the processing of cork.

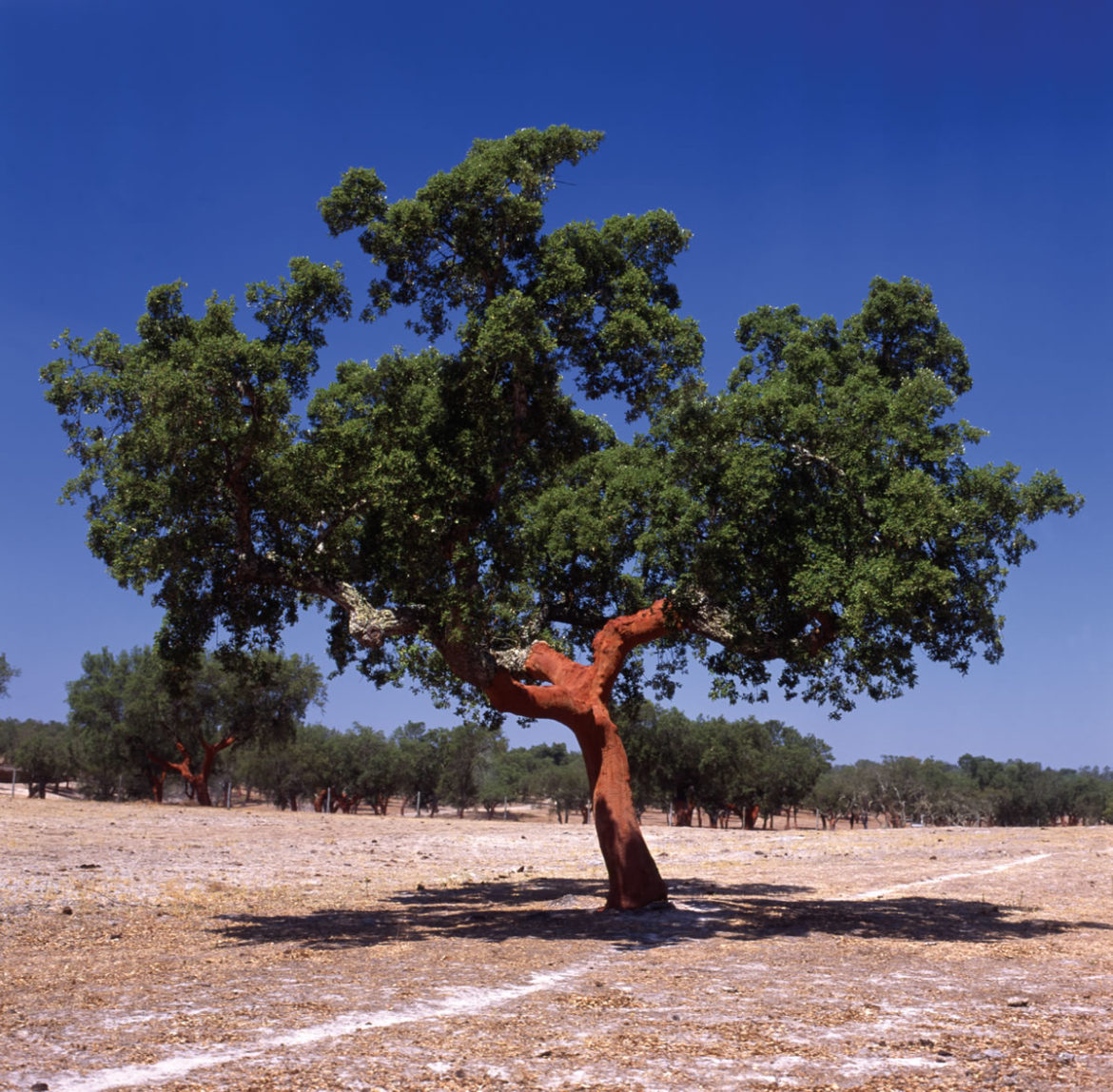

The harvesting of cork trees has been done in the same way for centuries and is unlikely to change, however the processing of cork bark has advanced unrecognisably in the last few years. The cork bark from Quercus suber trees goes through several selection processes – in the forest, in the processing plant, during stabilisation, during steam treatment and in the final cork production line – separated into several different grades of cork, of which only 5 to 10% will make the final cut for single-piece wine corks. And that small percentage comes after approximately 43 years of life as a cork tree in the forest.

The harvesting of cork trees has been done in the same way for centuries and is unlikely to change, however the processing of cork bark has advanced unrecognisably in the last few years. The cork bark from Quercus suber trees goes through several selection processes – in the forest, in the processing plant, during stabilisation, during steam treatment and in the final cork production line – separated into several different grades of cork, of which only 5 to 10% will make the final cut for single-piece wine corks. And that small percentage comes after approximately 43 years of life as a cork tree in the forest.

While some corks are still punched out into whole pieces by the traditional method, the rigorous testing of those corks now uses x rays, sensors (human, chemical and robotic) and pressure tests to spot any faults which may lead to TCA contamination, as well as a combination of five technologies that steam, treat and heat cork to remove all the volatile compounds.

“When I told my 89-year-old father that every disk now goes through an x ray, he thought I was crazy,” says Antonio Amorim, who is the fourth generation of the family business and has invested over €2.5m in the last year on eradicating TCA (including several of the €200,000 x ray machines). “But since 2009, the cork industry has started to grow again – by 4% in general and Amorim by 8%.”

The proof is in the pudding as they say, and the rigorous testing within the market too is showing results. All the natural corks that arrive to the USA for wine production are analysed on arrival and show a 95% reduction in TCA since 2002. This assurance does come at a price – the best tried and tested TCA-free whole piece natural corks will cost upwards of $0.50 cents per unit, meaning that it is only reserved for premium wines.

“Wines taste different when they are sealed with different closures, and I think some wines do taste better under cork,” says wine critic Jamie Goode, who tastes on average 9,000 wines a year. “The problem with cork has been its consistency, and the lower – still prevalent – rate of taint is troubling. But now there are lots of options open to winemakers, and it is almost a way of differentiating your range of wines: they might use screw cap for the entry level wines and cork for their top of range. Certain markets also demand certain closures.”

In a surprising turn of events, the use of cork in Australia is now on the up too. In spite of their reluctance to return to natural cork, Australian producers are bottling under natural cork once again for the Asian market – their biggest market today – as consumers associate cork with quality.

Drinking wine is, ultimately, all about pleasure. And although it might take some convincing to get some producers back on board with cork, for many consumers part of the pleasure of opening a great bottle of wine is hearing the cork give you that little celebratory Pop!

[/mepr-show]