It’s hard to imagine what Napa was like before it became Napa. I guess it was like Sonoma. But the ostentatious wineries and flush tourists that crowd Napa feel seem to be much more than 14 kilometres away from the farms and fruits stands that still hold fort in Sonoma. It feels somewhat implausible that it is only in the last 20 years or so that wine production in Napa has become more akin to a Hollywood production. Or so I gather from talking to some of the winemakers who have been there for longer than Screaming Eagle.

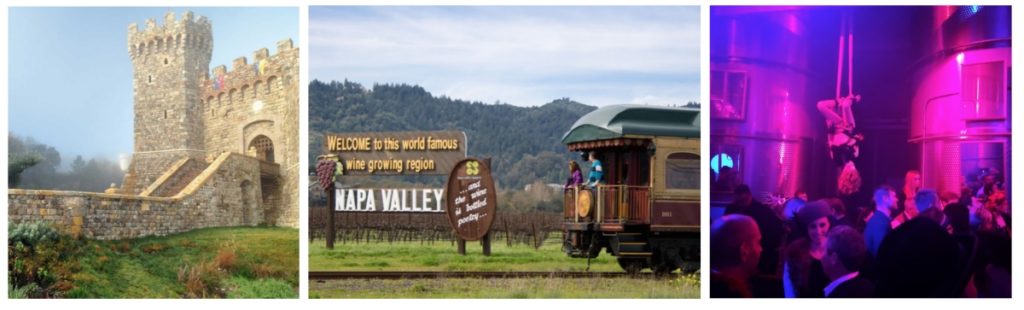

This isn’t my first time in Napa, but with 80 Harvests I’m on a slightly different mission. Last time – the first time – I came was in 2014, and it was my first taste of big Napa Cab. I wanted to be wrapped in its rich fleshiness, to taste the forbidden fruit and to feel the full-blown Napa-Disneyland experience. It’s a rites of passage for any New World wine journalist. And I relished in the fairyland castles, the toots of the tourist train and glamourous dancers gyrating between fermentation tanks. It was great.

But this time I wanted to know what makes Napa unique. And the thing about Disneyland is that it can pretty much be replicated anywhere, so while most of Napa’s show-stopping numbers leave you wide-eyed the first time, the second time you need more. I wanted to know who Napa was underneath that Mickey Mouse suit.

Napa Valley: God’s Greenhouse

So what is the real Napa, and what makes it unique?

Well the first thing viticulturist Steve Matthiasson asks me to understand is that Napa is a greenhouse. “Meteorologically speaking we have this really high pressure dome that blocks all the rain and clouds out. So this blue sunny sky here,” he motions overhead at the impeccably azure, cloudless ceiling, “is pretty much like this every single day. But it doesn’t get too hot either, because we get this marine influence.”

We walk over to the little vegetable patch in his vineyard in Oak Knoll. Excitedly he dives into a giant sprawling green plant, and after a moment of rummaging in the undergrowth, he holds out a perfectly pink and plump tomato, warm from the afternoon sunshine. I look at him, mentally quibbling whether I should ask to wash it first, but then I remember Steve Matthiasson is probably more organic than the water that comes out of the tap. “Bite it”, he urges me, taking a big gnash into his own pink tomato. A combination of aromas and flavours jump out at me as tomato juice dribbles all down my chin. “It’s sweet!” I spit at him, “now I understand why they say tomato is a fruit!” He just grins, and begins to forage for a chilli pepper. (Are we making salsa in my mouth?) Tentatively I take a bite from the bottom… It’s got spice, but it is almost as sweet as the tomato. “See?” he boasts triumphantly. “Greenhouse.”

He has a point. California has some of the best tasting tomatoes I’ve ever had. But how does this translate into wine? His basic point is that Napa isn’t just ripe for Cabernet. When we taste his wines in the garden, it beggars belief how few of his Napa wines actually have Cabernet in them. Or Merlot, or Chardonnay for that matter. As we taste wine after wine, the timber garden table is piling up with Ribolla Gialla, Tocai Friulano, Schioppettino… Are we in Napa anymore, Toto?

“Napa Valley used to have many, many different varieties,” Steve explains, opening another variety I can’t pronounce. “At To Kalon vineyard there were hundreds of different varieties they were testing. And a ton of them made great wine, and all the way up to and through the 60s Napa had many different varieties. And many white wines – we were actually more white wine producers than red wine producers here. We even had Chasselas!” His voice reaches an excited pitch, almost resembling a spirited yodel in the Swiss hillsides – the original home of this obscure white wine variety.

So how did Napa move from Chasselas to Cabernet? “It was in the 60s that French wines became popular with Julia Child and the Art of French Cooking. Then we started planting Cabernet.”

Steve Matthiasson and his growing wine family

Cabernet Sauvignon and the modern Napa identity

So we can actually trace the Napa Cab infatuation to, or even blame it on, Julia Child. But that would be forgetting the cataclysmic aftermath of the Judgement of Paris. Or so we are led to believe by the popular retelling of the now-legendary tasting.

If you haven’t heard of it, or watched Bottle Shock, British wine merchant – and now highly-regarded wine critic – Steven Spurrier rocked the very foundations of Old World wine sovereignty by putting on a blind-tasting in 1976 where several esteemed, mainly French, wine critics tasted Bordeaux versus Napa Cabernet Sauvignon and Burgundy versus Napa Chardonnay. The Californian wines triumphed in both categories, and that moment has metamorphosed through history into the great coup d’état of the New World overtaking the Old World in wine, with Napa wearing the crown.

Since then, life in Napa started to become Cabernet-shaped. From being a minority variety in the early days, Cabernet Sauvignon now claims around 40% of Napa’s plantings. ‘Its shining moment really started in the 1960s and it has gone nowhere but up from there,” winemaker Bob Foley tells me from his Howell Mountain vineyard – prime Cabernet territory.

Bob has seen the many different shades of Napa, as a wine consultant on the circuit for over 40 years: “In my early days as a winemaker in the 70s, we were still trying to figure out how the technology that was available or becoming available could make better wine. We had apple presses in the beginning,” he chuckles, “then we finally got wine presses. That was a big game changer.” This time he is dead-pan serious.

Since the apple presses progressed to wine presses, and all sorts of modern technology and knowledge came into play, the quality shot up. So much so, that the fastest growing price segments of Napa wine now are bottles over US$200, and those in the US$75-100 bracket. You might argue that some of that is based on Robert Parker-induced hysteria, but it is still impressive.

The dark side of success

The success of Napa is undoubtedly its greatest threat today. Everyone is so keen to jump on the Napa Cabernet train that the valley has become almost a complete monoculture. That has an important ecological impact and, while the sunny climes help protect it from many health issues, disease is rampant.

“Disease and pest control is a huge issue,” UC Davis’ head of viticulture studies, Dr Andy Walker, tells me as we sit through a particularly geeky interview at the leading winemaking school in the US. “We’ve had a number of unsustainable practises to try and control them all, so they’ve built up a lot of resistance.”

Disease and pests spread especially easily between vineyards in Napa because there are few biological corridors and natural barriers between vineyards. The image puts me in mind of kissing disease at university, once one person has it, everyone does. The living quarters are just too close together.

Pierce’s Disease is one of the biggest threats today as it, like phylloxera and nematodes, can kill vines completely. But Andy doesn’t see that as the greatest threat of all to California – he actually says the worst threat to viticulture right now is people. That’s quite a big statement from someone who studies plagues, diseases and other monsters all day.

California is bursting at the seams with an ever-growing population. It’s easy to get a sense of how unprepared it was for such an extreme growth spurt when you sit for hours in traffic jams. Fortunately Californians are ridiculously polite when sitting in traffic, but irrespective of this, they still consume water. And water – along with other precious resources – is becoming scarce in California’s wine regions.

As a beautiful hillside area with warm days, cool evenings, a greenhouse full of great food and yummy wine on tap, everyone wants to live in Napa. Demand for property has sky-rocketed. And when your neighbouring city is tech-heaven San Francisco, those property prices are high. Brain-achingly high.

So is Napa simply a game of thrones?

Finding an affordable piece of property in Napa is as rare as finding a dragon’s egg, or the the leprechaun’s pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. It just doesn’t exist for most of us terrestrial beings. You would have to be bankrolled by a Russian oligarch to be able to afford Napa prices today.

“It went from a sparsely populated farming community to an inundated tourist attraction and a millionaire’s – now billionaire’s – playground,” Bob explains, trying not to get irate, as we stand talking in the serenity of his vineyard. “I don’t care for that type of progress, but it’s the way of the world, and it’s the way it has gone.”

As I talk to some of the other longtimers in Napa, I feel a bit frustrated for them. It feels as if the long-standing community has put all their effort in getting Napa Valley into shape, out of phylloxera, and creating a bright and promising future together. And now Napa has gone and dumped them for a younger woman.

But that is the reality of many successful wine regions in the world and, unless you have more cash than everyone else, you either have to move on or make the best you can of it. “Change is something that is always going to happen, but managing that change and making it happen properly is really important,” winemaking consultant Mia Klein tells me, confiding that when she started in the 80s, Napa felt like a small backwater. Since then, the secret has well and truly got out. “It’s God’s country here; you realise it when you travel anywhere else,” she concedes.

It is no surprise that Napa has shot to stardom. After all, there is no nation quite as great at selling themselves as the US is, but Napa also has natural assets that makes it a world-class wine region.

Why Napa is unique in the world

“Napa Valley is a long skinny valley, but it has about half the known soil types in the world represented in this one place,” Steve explains to me as we talk about the amazing diversity of Napa. “And climate wise, we have the really cool mouth of the valley but it gets progressively warmer up the valley. You have all these different scenarios here, and Cabernet does well in them all.”

He goes on to compare the big, muscular wines from the eastern mountains with the edgy, savoury wines from the western mountains and the aromatic, elegant wines from the alluvial fans. “You can pick from these different areas and craft them together to make a layered, complex and complete Cab. It’s part of our tradition in Napa.”

The many different creases and intricacies of the valley is what has kept winemakers and grape-growers fascinated for decades. “Napa has the best of all worlds in terms of growing conditions for the finest wine grapes,” agrees Bob. “The soils and the climate, which is moderate, but we have enough heat to ripen grapes beautifully.” But it is his final point that resonates with me most: “My European counterparts tell me that one of the greatest attributes they see is the people and their willingness to share information.”

I couldn’t agree more. Perhaps it’s because I’m European myself. But it does feel like there is no other wine region in the world that has grown quite as fast and furiously as Napa. And I don’t think it’s just because of their savvy marketing, their proximity to the tech-mecca of San Francisco, or a blind tasting 40 years ago…

I think it’s because those founding farmers of Napa talked, shared and drank. In the same way that the winemakers and viticulturalists there still do today. The wine alcazars may be filled with fine dining customers, but you’ll find the winemakers at the taco truck around the corner, talking openly about their latest yeast strain or canopy arrangement, and giving pointers to their neighbours. I think the speed at which Napa has grown is due to the producers’ openness to the world, their generosity in sharing information and their desire to constantly get better. That makes Napa unique in the world.

This is a wine region that knows it can make great wine, and people aren’t afraid to talk about it.

–

–

More articles and videos on Napa Valley & California

- Interview on viticulture and variety with Steve Matthiasson

- Interview on Napa’s mountain valleys and wines with Bob Foley

- Napa’s Bordeaux Blends with Mia Klein: 360 degree video

- Zinfandel: The all-American grape with Carol Shelton

- The new frontier of Californian wine with Randall Grahm

- The different appellations of Napa with Mia Klein

- The geology and formation of Napa with David Howell

- Top 80: The 80 harvests wine awards

- The Lowdown on Lodi

- West coast wines & San Francisco scene with Alder Yarrow