This month I’ve been knee-deep in Uruguayan wine, researching a piece for Decanter (check out the South America edition this September!) which means I’ve been gum-deep in Tannat. While I normally reserve 80 Harvests space for the opinions of the winemakers and local experts, I wanted to share my reflections on whether Uruguay is putting its best foot forward with Tannat as their flagship wine. Comments (and arguments) welcome!

The tiny South American country is synonymous with this plucky variety that was first brought to its shores by Basque settler Pascual Harriague in 1870. Since then it has dominated Uruguay’s wine scene, accounting for up to 50% of plantations at its peak.

“Why Tannat?”, you might ask. Put simply, it is one of the most resistant varieties. Its roots don’t mind getting soggy and, come rain or shine, you’ll get a wine with colour, acidity and tannins. That’s an important factor to take into consideration for a nation which (unlike its South American brothers Argentina and Chile) receives an average of 1300mm of rain per year. The rest of the New World may produce fruit-bomb wines filled with sunshine and sugar, but Uruguay is an anomaly – more similar in climate to Bordeaux than Barossa. So Tannat triumphed and took over as the wine that delivered every vintage.

Until the 90s, the majority of Uruguayan wine was your average plonk. It was table wine, made with a backbone of Tannat (to add some structure and use the fancy vitis vinifera name) blended with cheaper, and more abundant, hybrid varieties. Uruguayans like to drink (they have the highest per capita consumption outside of Europe) and this was the sort of wine you could knock back cheaply and drink from large carafes. There is nothing wrong with that, but when wine imports started flooding in from mega-producers Chile and Argentina in the 90s, many locals switched to the cheap and cheerful wine coming from the neighbours who could afford to make smaller margins on bigger productions.

Uruguay had to catch up, and so it modernised. New technology and techniques came in along with a flock of flying winemakers. Hybrid varieties were ripped out, and the only real contender to make its mark from the vitis vinifera family was Tannat.

Argentina had already cornered Malbec, and Chile had planted huge swathes of Cabernet Sauvignon and Sauvignon Blanc, so Uruguay decided to wave the flag for Tannat, a variety that had stood fast for centuries.

But is Tannat sellable?

In a discussion with international winemaker Alberto Antonini, he seemed to think it isn’t . Niche, but not commercial – and he should know, as he sells wines from Italy, Australia, Chile, and even Armenia.

“I like Uruguayan Tannat for its rusticity,” Antonini told me, “I think they are very genuine wines but they are not designed for a wider audience. It’s a great grape in potential spices and flavours but it is not an easy grape to work with because it has got very strong and difficult tannins… it’s difficult to make Tannat approachable.”

The strong tannins may make Tannat the healthiest wine in the world (it’s the variety with the greatest source of procyanadins don’t you know?) but medicine isn’t always easy to swallow. And Tannat is one hell of a variety to tame. Which is what makes Uruguay’s attempts over the last two decades to master the variety so admirable, and makes the results all the more impressive.

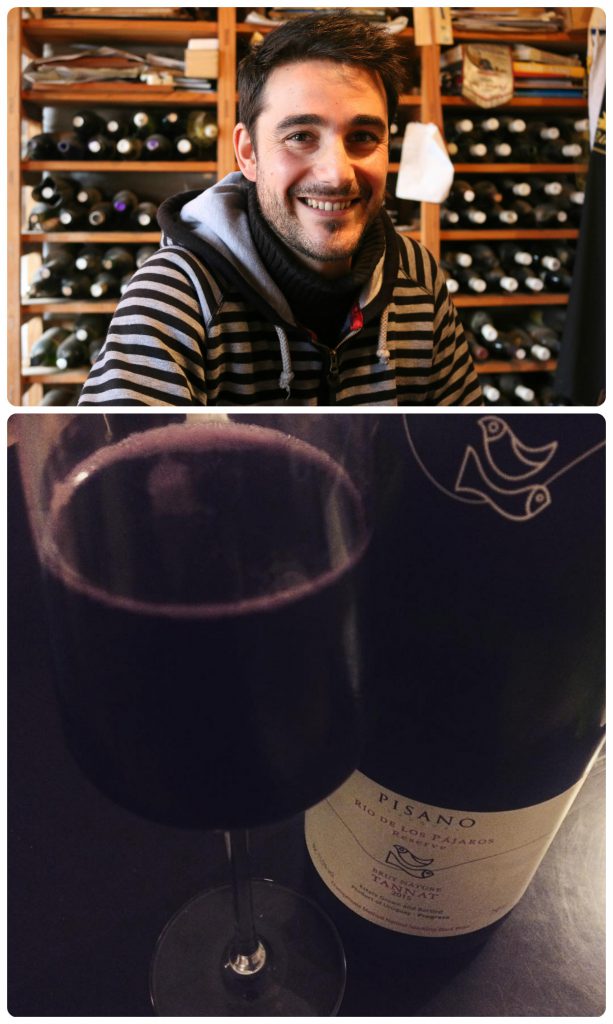

Take for example young gun winemaker Gabriel Pisano: he began experimenting with old-vine Tannat grapes fermented in open barrels. He found the result much smoother, aided by further micro-oxygination in neutral barrels. “I think the quantity of oxygen makes the difference,” says Gabriel. “You can have the fresh fruit, without needing to over-ripen the grapes, and still have the round tannins.”

Take for example young gun winemaker Gabriel Pisano: he began experimenting with old-vine Tannat grapes fermented in open barrels. He found the result much smoother, aided by further micro-oxygination in neutral barrels. “I think the quantity of oxygen makes the difference,” says Gabriel. “You can have the fresh fruit, without needing to over-ripen the grapes, and still have the round tannins.”

It works, and you can taste the proof in Viña El Progreso‘s wine, Sueños de Elisa. Another winery working with open fermentation tanks is the traditional family producer, Bodegas Carrau, who have been making their top Tannats this way for years – you only have to taste the juiciness and tension of the winery’s icon wine, Amat, to understand.

Winemakers such as Pizzorno took Tannat to a different level when they tried out carbonic maceration – making a great lunchtime Tannat, drink it chilled with lashings of lasagne. The dry (and red) sparkling Tannat by Pisano is another shining example of Uruguayan Tannat reinvented.

Producers have been focusing on everything from their canopy management to the length of oak-ageing to learn the art of producing a balanced Tannat. That balance is also often achieved through blending. Some of my favourite blends from amongst those I recently tried in Uruguay included Tannat blended with Nero d’Avola and Sangiovese at De Lucca; a Tannat-Viognier blend at Alto de la Ballena; a Tannat-Pinot Noir blend from Marichal; and Viñedo de los Vientos make two interesting blends with Nebbiolo and Ruby Cabernet.

The other great shift you can feel and taste in Uruguayan Tannat is to do with location. Uruguay’s wine production has historically been concentrated in Canelones, just outside its port-city capital Montevideo. Undoubtedly the establishment of Canelones as the wine capital was due to its proximity to the market (over a third of Uruguay’s population live in Montevideo).

Don’t get me wrong, there are some great vineyards and wines coming out of Canelones but it has its problems. The heavy soils make it hard to produce certain varieties that need better drainage, and in wet years all varieties suffer somewhat. Familia Deicas have even gone to the extremes of covering their vineyards with plastic sheeting to protect them on particularly rainy years – a method that is both costly and a little bit loco, reserved only for their very best and very oldest vines. It’s the equivalent of Tannat wearing a designer raincoat.

When push comes to shove though, if you were given a blank cheque today to start a winery anywhere in Uruguay – chances are you wouldn’t pick Canelones. And that’s exactly what is happening with new investments in the country.

It has really only been in the last decade that wineries have ventured outside of Canelones for commercial winemaking, and we are just beginning to see the tip of the iceberg when it comes to potential vineyards sites in Uruguay.

There are already exciting developments in the riverbeds of Carmelo, the schist hills of Mahoma, the warm midlands of Villa El Carmen, and along the rocky coastal hills of Maldonado. Each of these micro regions is bringing a totally different profile to Uruguayan Tannat.

“Uruguay is interesting because there is a lot of excitement,” flying winemaker Paul Hobbs told me, as he prepares to launch Uruguay’s first single-vineyard collection of Tannats from around Uruguay with Familia Deicas. “There are great terroirs that people didn’t know about. Today there is a new energy!”

But the excitement isn’t just about Tannat. Uruguay has a huge potential for white wines with a character that you just don’t find in many other South American regions. The warm, wet climate allows for aromatic wines with attractive acidity, without having that overwhelming freshly-cut grass style.

“It’s too warm for New Zealand-style Sauvignon Blanc,” explains Duncan Killiner, a Kiwi winemaker who was initially brought into Uruguay with precisely the goal of helping make more commercial, New Zealand-style, Sauvignon Blanc. He found conditions that were different to other New World countries, offering the chance to make an altogether different style of whites: “The white wines are more Bordeaux style – the warmer nights mean you lose that green style. The wines are more fragrant and voluminous.”

My favourite whites from among those I tried last month were rather exotic varieties for South America: Albariño, Arneis, Marsanne, Petit Manseng, Riesling and Viognier. And of course there were good Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc wines too.

My favourite whites from among those I tried last month were rather exotic varieties for South America: Albariño, Arneis, Marsanne, Petit Manseng, Riesling and Viognier. And of course there were good Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc wines too.

Outside of whites I tried interesting Cabernet Franc, Syrah, Petit Verdot, Pinot Noir, Zinfandel, Merlot, Tempranillo, Marselan, Arinarnoa… The list was almost endless.

While I can’t drink Tannat every day, I would be happy to drink Uruguayan wine everyday. There’s an explosion of diversity in place and variety to taste.

Is Uruguayan Tannat old hat? No. It’s seen a renaissance, a modernisation and a diversification. There are great Tannats being made in Uruguay. It is exciting. However, what I hope we don’t see is a pigeonholing of Uruguay as solely Tannat producers. It is much more than that and, if Uruguay wants to wed with the new generation of millennials, it needs to bring out more than one hat. We want to see that entire multi-coloured wardrobe of varieties and regions that makes Uruguay one of the secretly best-dressed wine countries in South America today.

4 comments

I’m a fan of Tannat from Uruguay (I like a good steak too!) You’ve definitely made me want to try more, and some of the other wines they make there too. Good article.

Thank you Thomas. There is definitely a lot to explore in Uruguayan wine! Enjoy the ride 🙂

Good information. Lucky me I stumbled upon your website. I have bookmarked it for later! When do you come to Australia?

We’ll be in Australia in 2017! If you have any suggestions or favourite Australian regions please let us know – feel free to comment here or on social media @80harvests. Cheers!